What Are Sea Caves and How Do They Form?

The sea caves in Cornwall, along with the towering cliffs that surround them, have been sculpted by countless centuries of Atlantic swell battering the coast. Caves in Cornwall range from small grottos hidden in narrow zawns, to vast cathedral-sized caverns that echo with the sound of the surf. Cornwall caves are dark, mysterious, and accessible only in calm conditions; they are the final frontier of the Cornish coastline.

Most sea caves are what geologists call littoral caves, formed in the high-energy zone where the ocean meets the land. Waves, driven by wind and tide, relentlessly carve into the cliffs, wearing away weaknesses in the rock. The seas are rarely still, and nowhere is this truer than on the wild Atlantic coast of west Cornwall, home to some of the most dramatic coastal caves in the UK.

Protruding into the Atlantic Ocean, Cornwall has nowhere to hide from ocean swells. The action of wave on rock is unceasing, interspersed with occasional storms of such freocity, that they can bring entire sections of cliff down in a single night.

As we explore the coastline, especially after our winter layoff, we often notice new rock scars and collapsed sections where the sea has once again reshaped the cliffs and deepened existing sea caves.

The winter of 2013–14 is particularly memorable. One storm after another pounded the Cornish coast, sending swells of up to forty feet crashing against the granite. When spring arrived, huge sections of cliff had fallen into the sea, a powerful reminder of the natural forces that continue to sculpt Cornwall’s coastal caves today.

Sea Caves in Cornwall: Faults and Veins

Waves do not act equally on the cliffs they strike. Variations in aspect, rock type, and the natural planes of weakness within the rock are all exploited by the sea. As a result, some sections of cliff erode far faster than others, creating the intricate patterns of sea caves in Cornwall that line its coast today.

The result is the impossibly complex coastal landforms we see today. Rather than uniform, uninspiring flat walls of rock being eroded equally, we see headlands and bays, promontories and coves, as well as sea caves and arches.

The formation of coastal caves is greatly accerlated by the exploitation of planes of weakness in the rock. These may be geological faults in the rock, or where two different bands of rock intersect, or where a fault has been intruded with igneous rock to form a vein or a dike.

The Penwith Peninsula is a perfect example. Much of this area is made of the Land’s End granite, part of the vast Cornubian granite batholith that extends east to Dartmoor and west to the Isles of Scilly. This ancient formation owes its existence to immense tectonic forces that shaped Cornwall over millions of years, leaving behind the faults and fractures that now guide the sea’s relentless erosion.

Along with these faults came countless mineral veins and dikes that cut through the Cornish cliffs. These features not only created the lodes that made Cornwall famous for tin mining, but also formed the natural weaknesses that allow the Atlantic to carve some the most dramatic coastal caves in the UK that we can see today.

The Growth and Collapse of Sea Caves

As sea caves grow over time, their expansion is eventually limited by natural forces. Boulders that fall from the ceiling can act as breakwaters, reducing the energy of incoming waves and slowing further erosion.

As roofs widen and become increasingly unsupported, they may collapse entirely. This can lead to new features we can classify them as. If the back part of the cave falls in, but the roof around the mouth remains intact, we may get a ‘collapsed cave’. A striking example is Funnel Hole at Gwennap Head near Porthgwarra, one of the most dramatic collapsed coastal caves in Cornwall.

If the sea cave’s entire roof collapses, we may get a narrow zawn, usually with a floor choked with large boulders that once made up the roof. At the back of these zawns, what’s left of the cave may continue cutting its way into the land.

Great examples of this occur at Dutchman’s Zawn, south of Land’s End, for example. Another example you can visit on coasteering adventure with us, is the huge cave at the back of Lead Zawn at Pendeen.

Thus, in contrast to solution caves that form in limestone and can be many kilometres in length, sea caves are typically much shorter. They usually range from a few metres to a few tens of metres in length.

Cornwall has more than its fair share of respectably long sea caves. The huge Pendower Cavern might be pushing the 100-metre mark. There are also many contenders on the north coast of Cornwall.

How Long Can Sea Caves Get?

On a global scale there are only 108 sea caves currently recognised as being over 100 metres in length. Do note, that lack of formal surveying and exploration means there are undoubtedly many, many more.

At the present time, the longest known sea cave in the world is a staggering 1540 metres in length. It is the Matainaka Cave, Otago, on New Zealand’s South Island.

While it’s not formed entirely through littoral erosion like Cornwall caves, it is thought that solution processes, associated with more traditional cave formation, played a large role. It’s an amazing discovery and must be an incredible place to explore.

Our Top 10 Sea Caves in West Cornwall

But, as they say, it’s not just about the length. The following list of the best sea caves in west Cornwall is highly subjective, chosen from a mix of factors that make each one special. Many of these Cornwall caves are impressive in scale, but size alone isn’t everything.

Aesthetics play a big part. Sea caves in Cornwall can be mysterious, colourful, and beautiful places, with formations that catch the light in unexpected ways or display streaks of vivid minerals across their walls. Each cave has its own atmosphere, from the echoing cathedral-like chambers to the tiny hidden grottoes that only reveal themselves on the lowest tides.

Another factor in choosing these caves is the sense of adventure involved in reaching them. Most of the coastal caves on the following list can only be reached by coasteering, and can be great rewards for some adventurous coastal exploration. Some of the caves are at the opposite end of the size scale, and stand out for their unusually diminutive size.

Some entries here represent entire stretches of cliff where several outstanding coastal caves occur close together, making it impossible to pick just one.

As ever, this is not a guide to use to go and find these caves yourself. Many of them are in extremely remote locations and can only be accessed rarely due to their exposure to swell. Some of these caves are features of our guided coasteering routes, so if you want to visit some amazing Cornish sea caves, get in touch to join us for an unmissable coasteering adventure.

10. Funnel Hole, Gwennap Head

Funnel Hole at Gwennap Head, near Porthgwarra, is one of the most dramatic sea caves in Cornwall, and a textbook example of a collapsed cave. The headland’s older name, Tol-Pedn-Penwith, Cornish for “the holed headland of Penwith”, is a clear nod to this incredible feature.

An archetypal collapsed cave, as the cave grew in size beneath the headland, the roof eventually lost support and fell in. The bridge above the mouth of the cave has remained intact, and the resulting funnel-shaped feature plunges approximately 30 metres from the grassy plateau above, down to the boulder-strewn cave bottom below.

Being adjacent to the southwest coast path, and only a short walk from Porthgwarra, this impressive feature is probably the best-known cave on this list. Scores of visitors visit it every year, and carefully walk around the rim trying to glimpse the bottom, far below.

However, the approach to the cave below never dries out, even on the lowest spring tide. Therefore, seeing the collapsed cave from below is enjoyed by only a select few. The next best vantage point can be gained by climbers climbing in the Pinnacle Gulley area of Chair Ladder, from where it is possible to look straight into the cave from afar, without being able to see the daylight coming from above.

I had a particularly hands-on experience with Funnel Hole when two amateur drone pilots lost their craft down the blowhole. They attempted to fly the drone down the hole, but were completely unprepared for the concentrated updrafts speeding through the feature. In desperation, they searched for a local climbing guide to see if the drone could be rescued.

A short while later, I ascended the rope from the bottom of the hole to reunite the craft with the owners. I myself had probably gained one of the most thorough visits down the shaft that anyone has ever had. I also learnt first-hand the extrenely firable nature of the rock — the very reason the cave formed here in the first place!

The cliffs around Gwennap Head have also served as a stunning filming location for the BBC’s adaptation of Poldark, with Funnel Hole’s wild backdrop perfectly capturing the drama of Cornwall’s Atlantic coast.

9. Rinsey Head

Just to the west of Praa Sands is the headland of Rinsey Head. The headland is most recognisable for the lone house situated close to the edge of the precipitous granite cliffs. The large house, situated in private grounds, must be one of the best-situated residences in Cornwall. It is available to rent as a holiday home, so if you would like to find out more, contact stylishcornishcottages.co.uk.

What most visitors don’t realise is that hidden directly beneath this headland are some of the most impressive sea caves in Cornwall. Invisible from above and unreachable on foot, these Cornish caves can only be explored by coasteering, stand-up paddleboard, or kayak.

The caves consist of a complex through-cave, as well as a pair of relatively deep caves, carved out of some remarkably textured granite. The caves may be as much as 40 metres in depth and culminate in low roofs. They are sandy bottomed, thus at low tide may offer some truly hidden beaches where you’d definitely struggle to get a suntan.

The area around Rinsey is well worth a visit. The beach at Porthcew is uncrowded and there’s a wealth of mining heritage to peruse. Above the beach is the restored engine house of Wheal Prosper, a short-lived tin and copper mine that had a brief life from 1860 to 1866.

A short walk further east, towards Porthleven, you will encounter the impressive engine houses of Wheal Trewavas, with the shaft of Old Engine Shaft being possibly the only mine you can coasteer into!

It is in this area that we also run most of our beginner rock climbing courses, so we recommend you take a day here, soaking up the wonderful scenery, whilst trying your hand at climbing Cornwall’s wonderful granite.

8. Prussia Cove

It’s unlikely that the ruler of a German Kingdom in the eighteenth century would be the source for the name of a cove in Cornwall, but that’s apparently what happened. Infamous Cornish smuggler, John Carter, ran various smuggling rackets in the late 1700s from his base on a secluded spot of the south coast of west Cornwall. Who knows, maybe he even used the area’s many coastal caves as places to stash his wares?

According to his brother’s account in ‘A Cornish Smuggler’, John Carter looked so like Freidrik II, King of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, that he acquired the nickname the ‘King of Prussia’. How this was so established in the age before photographs were widely circulated, we’ll never know. But, by the time of Carter’s unexplained disappearance, and presumed death in 1807, his smugglers’ hideout had acquired the name Prussia Cove.

Still providing relative peace and quiet, the area is popular with those who know it, for its beauty. With so many stunning coves and beaches to choose from in the area, you know it must be good. Despite having little sand to offer beachgoers, the rocky slabs of the four smaller coves that comprise Prussia Cove, do get crowded with people.

The area offers some good coasteering, and we use the site occasionally for our coasteering trips. As well as offering an array of fine cliff jumps and features, the highlight of coasteering at Prussia Cove is the opportunity to visit some of the most picturesque sea caves in Cornwall.

The westernmost cove is home to a pair of huge, high sea caves. The water in this cove is shallow and sandy and on sunny days, the quality of light is such that, it’s easy to imagine you’re in the tropics. Indeed, the cove and its caves would have made a fine location for a scene from the Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise.

The right-hand cave, as you look at the cliff, is the deepest and I’d estimate it to be up to 60 metres in length. Land-lubbers do make visits here when tide allows, so it is an extra-special treat when you coasteer into the cave and are the first to leave footprints in the sand that day.

In the same area is a tiny cave I call the ‘oubliette’, a tiny dungeon-like hollow where you put someone to forget about them. Completely undetectable from afar, this diminutive space is reached by shimmying along a narrow crack, before ducking under a low roof. Once inside, there’s a small sandy beach and just enough room for a small group to assemble, sitting room only!

Make sure you’re there at low tide, as the place is completely underwater at high tide. It is also impossible to access in all but calm conditions. It’s a tiny, and frankly unlikely place. We’d been coasteering at Prussia Cove many times, completely overlooking it, until we discovered it one day by accident.

7. The Cave of Many Colours, Cape Cornwall

A closely-guarded local secret, and one that can be accessed on foot, I shall not reveal the location of this sea cave here. The closest I’ll say is that it is somewhere near Cape Cornwall. Despite being accessible on foot, it can only be reached at low tide and in calm seas. Either misjudging the swell or the tide could result in one being totally stranded here.

This narrow cleft in the cliff does exactly what it says on the tin — its walls are painted with almost every colour of the rainbow. If you know the cave’s aspect and time your visit for when sunlight shines directly inside, the results can be breathtaking. It’s one of the most striking sea caves in Cornwall, and easily one of the most colourful.

The cave is in granite, but almost every surface is some, almost unnatural-looking hues, chiefly reds, purples, greens and oranges. The source of these pigments is from various minerals leeching through the rocks and being precipitated on to the cave walls. When you consider that the cave is deep in the heart of the former St. Just metal mining district, it’s no surprise to see such extensive mineral deposition.

So far, many of the sea caves we have looked at are quite well-known, at least to Cornish locals. But as we move down the list, the remaining caves are well-hidden, in remote places, and only accessible by adventurous means!

6. Carn Barra

Like many of the Cornwall caves that follow in this list, this cave is notable simply for its size. Located in the environs of Carn Barra, between Nanjizal and Porthgwarra, access is by coasteering or sea kayak only. With no nearby easy launch, it would be a very arduous paddle to reach this cave by SUP.

Coasteering access is easy, if you know where to launch from. The cliffs in this whole section of coast are largely very steep with few ways up or down. Only with detailed local knowledge can you get close enough to be able to coasteer into the Carn Barra sea caves without having to cover miles of terrain.

The morphology of this cave is typical of the large coastal caves of west Cornwall. Tucked at the back of a deep zawn, the huge mouth of the cave is overhung by huge, jagged, gravity-defying granite blocks. As you hurry past these you finally end up on the boulder beach at the back of the cave.

Completely rounded from aeons of being tumbled against each other during stormy seas, it’s worth noting that these rocks probably fell out of the roof above your head…

In the same area is another worthwhile cave. Though nowhere near as large as its neighbour, this cave is tall and narrow. Its narrowness means it concentrates waves as they enter it, resulting in a bumpy ride, even on a calm day. The closeness of the walls allows you to get a great appreciation of the amazing textures of the rock and the amazing variety of colours from the various seaweeds and algae that festoon the walls.

The Cave of Many Colours may be one of the best known locally, due to its ease of access. But all of these sea caves, particularly the ones in granite it seems, offer a wild, often psychedelic palette of colours.

Carn Barra is one of many isolated headlands on the stretch of coast between Porthgwarra and Land’s End. This area is, in my opinion, the finest stretch of coastline in all of Cornwall. I’d go as far as to say that a coast walk along this stretch is a must do. Take a picnic and plot up at a spot where you can admire the golden, castellated granite cliffs and watch the Atlantic rollers make their way in.

5. Carn Naun Point Double Cave

What a discovery this was! This cave offers two for the price of one. Two converging fault lines have been eroded away. The result is two caves that meet inside the cliff, forming one large chamber. The rock architecture is stunning. The various ledges in the middle, and around the edges of the cave give the place an almost amphitheatre-like feel. It’s one of the most unusual sea caves in Cornwall, formed where two faults meet.

In terms of its location, this cave couldn’t really be anywhere more remote. It’s somewhere in the area of Carn Naun Point. Carn Naun Point is pretty much smack-bang in the middle of St. Ives and Zennor. These are the only real access points for getting to this 6-mile stretch of coast. Even walking here is a bit of a mission, let alone coasteering here.

This double sea cave is not near any easy way up or down the cliff, so it really is a true hidden gem. It was definitely a massive reward to find it when we were coasteering along this section of coast for the first time.

4. Dutchman’s Zawn, near Carn Barra

Dutchman’s Zawn is also in the area of Carn Barra, but this cave earns its own place on this list. Bigger and more impressive than the other caves at Carn Barra, everything at this cave has been ‘turned up to 11’!

Situated at the back of a large, shallow zawn the mouth of this caves towers some 20 metres or so above the water. All the usual features apply, just on a grander scale. As you reach the boulder beach, you have to negotiate car-sized boulders to access the back of the cave.

It’s a humbling reminder that, whilst we visit these places when the seas are calm, it’s when the seas are at their most ferocious that most of the work of eroding out these gigantic caverns is done. It’s simply impossible to imagine the scenes that take place in these caves when a spring high tide coincides with a monstrous winter storm swell.

At a guess, the cave must be about 20 metres high for much of its length, and its length must be approximately 50 metres. This certainly makes it one of the most voluminous caves in west Cornwall and one of the standout sea caves near Land’s End.

This whole section of coastline is popular with rock climbers, and the extensive crag at Carn Barra attracts many local and visiting climbers to enjoy its quality rock climbing. Dutchman’s Zawn itself also offers rock climbing routes. But, due to the acquired taste of its rock quality and the difficulty of most of the routes here, it receives almost no visits.

The climbs here were all developed by the father and son team of Rowland and Mark Edwards. The duo ran their Compass West climbing school from their base in Sennen for many years, before finally deciding the Cornish summers didn’t make up for the relentless Cornish winters, and permanently re-locating to Spain’s Costa Blanca.

Both in Cornwall and Spain, they, quite literally, left no stone unturned in their quest for new routes. They did first ascents of thousands of routes in west Cornwall, including what still remain the hardest routes in the area to this day.

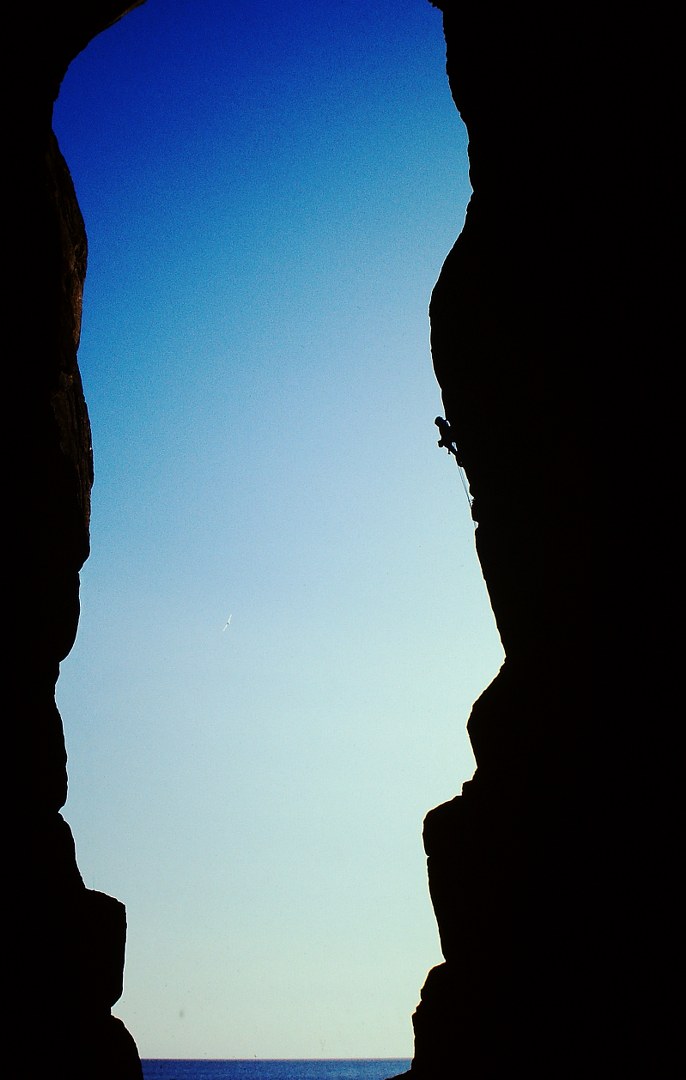

The photo below shows Mark Edwards on the first ascent of Eat ‘Em and Smile, E6 7a. The route takes a direct line up the steep northern wall of Dutchman’s Zawn, on less-than-perfect rock. This is one of many of Mark’s routes on the Land’s End peninsula that has yet to see a repeat (photo by Rowland Edwards).

The towering walls above the zawn hide one of the grandest sea caves in Cornwall, an unforgettable place to visit by coasteering.

3. The Great Cave, Land’s End

Let’s crank things up yet another notch and visit the Great Cave at Land’s End. Lying just to the north of Dollar Cove, and just south of Dr. Syntax’s Head, the cave is tucked away under Land’s End’s towering cliffs, and is completely undetectable to the tourists milling above. This sea cave cannot be seen from any angle, until you are facing its ominous-looking entrance at sea level.

Unlike the huge cave at Dutchman’s Zawn, which holds no secrets with its entrance being the maximum height of the cave, the mouth of the Great Cave is relatively modest.

If the cave remained this size, it would still rank as a very fine sea cave. However, once through the opening, the scale of the cave is quickly revealed as it quickly expands in all directions. The chamber is jaw-droppingly huge, and the space is closer to cubic in shape, i.e., with its height, width and depth being much closer to equidistant than a typical long and narrow cave.

The result is an epic cavern of cathedral-like proportions. I would guesstimate that this Cornwall cave may be as much as 40 metres across, along any axis.

This is one of a few sea caves on this list that you can visit with us. It is one of the highlights of our Advanced Coasteering at Land’s End tour. If you fancy being one of a select few to have ever witnessed this natural wonder, then get in touch to organise a trip with us.

Apparently, there was a time when the owners of the Land’s End tourist attraction had a plan to make the cave a visitor attraction. It was proposed that a tunnel be blasted and the Great Cave be made easily accessible from above. It certainly would have been a very impressive attraction for the masses and made it one of the most famus caves in Cornwall.

I must say, though, I’m glad the plan never came to fruition. It makes it all the more special that just a select few coasteerers and kayakers are the only ones who ever get to experience the awesome Great Cave of Land’s End.

2. Pendower Cavern, near Land’s End

In remote west Cornwall, south of Land’s End the peaceful bay of Pendower Cove is nestled in between the mighty headlands of Carn Barra and Carn Les Boel. These ancient Cornish place names translate as ‘Higher (or possibly loaf) Headland’ and ‘Headland of the Bleak Place’, respectively.

Pendower Cove is a quiet place, and with its lack of a sandy beach and awkward access, most people who come this way see no reason to explore this cove any further. Yet, this isolated bay is home to some of the largest sea caves in west Cornwall.

Formal surveying would be a very worthwhile undertaking here, as I’d estimate that the cave must be approaching 100 metres in length. It does become hard to judge once you near the back of the cave and the entrance is just a tiny pinprick of light in the distance.

Admittedly, I lack a waterproof torch necessary for getting the most out of these cave explorations. There are a great many where I haven’t quite reached the back. You can often find it by fumbling around in the dark, but it also likely that there is a continuation of the cave that you never quite find.

The cave’s height and girth are impressive on their own, but its length is stupendous. It simply keeps on going and going. I have only been to the back of the cave at low tide, when the cave is mostly dry.

It would be a very eerie experience indeed to make for the back of the cave when the tide was in. The higher water level would greatly reduce the amount of light able to penetrate the sea cave, and floating around in the black waters would, I’m sure, play all sorts of tricks with the mind. Mind games aside, meeting a seal in the darkness could be a very unpleasant experience for you both!

The bay is a popular hangout for seals, and you’ll often see one or two swimming about in the cove, or ‘bottling’, a characteristic behaviour when a seal floats, often vertically, with its nose sticking up into the air. This is how seals like to relax and rest between foraging trips, which can take them out to sea for days at a time.

Anyone entering the water at this area should be mindful of disturbing the seals who congregate here, and are particularly fond of hauling out in the large caves found here. It is especially important to avoid visiting such areas during the seals’ pupping season, which is mostly from October to January, but may begin earlier and finish later for some pinniped parents.

Honourable Mention: The Breath of Poldark, Trewellard, Pendeen

Before I reveal my favourite sea caves in west Cornwall, an honourable mention must go to the following caves we discovered on the north coast of Penwith. These Cornish caves are located in the heart of the Tin Coast, an area so named for its rich tin and copper mining heritage.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, mines here, such as Botallack and Levant, were world pioneers in developing submarine mining. The adventurers (as the mine owners were called) sought to exploit as many of the mineral lodes as possible, even those stretching out far beneath the sea.

Thus, these mines tunnelled their way seaward, and it is said that the miners could hear the waves crashing above their heads as they went about their subterranean business.

This small cluster of sea caves are notable for a shared idiosyncrasy. They are not extensive in their development at all, and on that merit alone, they wouldn’t get a mention.

However, three neighbouring caves here all seem to share one unusual feature. They all have a tendency to strongly backwash incoming waves, often accompanied by large plumes of spray as water and air are compressed into their cavities.

The largest and most impressive of these was named the ‘Breath of Poldark’ by Kernow Coasteering guide, Lee. Although not deep at all, it’s a ridiculous space, with only a tiny amount of space available between the water level and the roof. It is this narrow pocket of air that so consistently gets blasted out, along with sea spray, to create the breath of Poldark.

In addition, the cave has a streak of luminous green mineral staining running down one side of its mouth – a clear indicator of its proximity to a metal mining area. Of all the mineral formations I have seen, this is the most fluorescent, and it looks like something Slimer from the Ghostbusters might have deposited there!

There’s great fun to be had here, as a sizeable cliff jump is available right above the cave. If you time your jump with the explosion of spray from the cave, the results are quite spectacular!

The cliffs above the Breath of Poldark are extensively stained with green and blue copper minerals, and are an impressive feature in their own right.

The two neighbouring caves are smaller. One, was discovered on a subsequent visit and was quickly named the Breath of Demelza. This cave is deeper, but the back could not be reached due to her violent and antisocial spitting habits!

The final swashing, burping cave was adorned with the most psychedelic pink seaweed I’ve ever seen. All in all, quite a special little area to explore by coasteering.

1. Trevean Cliff Caves, Morvah

At last, we reach my favourite sea caves in west Cornwall. Part of their appeal is their absolute remoteness. They are located on a particularly lonely section of the north coast of west Penwith. There is no way of viewing them from the land, so their existence would only be known to those who have toured this coast by sea, whether it be by boat or sea kayak.

Coasteering to these coastal caves is awkward, as access and egress up and down the cliffs is very limited hereabouts. The first time I discovered these caves was on a marathon coasteer all the way from Portheras Cove, near Pendeen, to the mighty headland of Bosigran, which sits underneath Carn Galver.

This was an epic journey that took five hours to complete. By the time we reached these caves, weariness had firmly set in, and the first two of the caves we bypassed altogether. When I later revisited the area, it’s easy to see why. The first cave you come upon is quite humble in appearance. Its aperture is very narrow, although it is tall. At first glance you would not expect an extensive cave to have formed here.

As you continue through the entrance, the sea cave continues, remaining quite narrow. Slowly but surely, the roof gains height and the walls widen. Looking backwards, you can now see that the profile of the cave entrance resembles a giant keyhole.

Presently you find yourself in a round pool. The back wall, however, is not the end of the cave. This wall is several metres high, and consists of extremely slippery, wave-washed granite. Only a determined effort enables one to find a line of weakness and climb up on to the platform behind.

It’s only once on top of the platform that the scale of the sea cave can truly be understood. The platform is a huge area, and continues backwards, cutting into the hillside. Unexpectedly, the cave forks into two, with each fork continuing farther back again. In particular, the right-hand fork is very long indeed.

As ever, the lack of some kind of torch prevented the full extent of the cave to be properly ascertained. As you head back towards daylight, you can enjoy a few final moments promenading on the large platform before plunging into the pool and heading back out into the world once more.

I would imagine the numbers of people who have visited this Cornish cave is extremely low. Out of those who have, they would have almost certainly been sea kayakers, who reversed their craft into the pool for a quick look around.

Due to the difficulty of climbing up on to the platform above, and for fear of losing their craft, I would not be surprised if no other humans had ever set foot on the platform at the back of this cave, making this a very special find, indeed. I would suggest that more people have walked on the moon than have set foot at the back of this sea cave!

The surprising architecture of this cave, combined with its secret location and low number of visitors, makes this my overall favourite west Cornwall sea cave and one of my favourite caves in Cornwall.

But we’re not done yet. Including the cave above, there are three sea caves in close proximity here. The middle cave is long, with a low roof and a sandy bottom. A very impressive cave in its own right, it is a nice bonus, but no competition for its bigger brother next door.

The final cave doesn’t try to compete in size. But it does compete in its weird and whacky architecture. This sea cave consists of several adjoining chambers. To gain entry, you have to duck under a small rock arch and squeeze along a short cleft, only just large enough to turn sideways and squirm down.

This brings you to the ‘waiting room’, or antechamber, from where the final section of the cave can be accessed. The antechamber is a bowl-like feature, surrounded on all sides by smooth, wave-washed walls. At the back of the chamber is a wall with another cleft in. The bowl-like nature continues above this, as the rounded ceiling balloons upwards and backwards.

Awkward squeezing and udging gets you into the final section of the sea cave. From here, the cave is extremely narrow and dark. We didn’t reach the back, due to the complete lack of light. I suspect that the cave doesn’t go too much further. This is definitely one of the weirder cave experiences on offer in west Cornwall and, again, I’d be very surprised if any other people have wriggled their way into the back section of the cave before.

These three coastal caves together make what is, for me, the best sea caving adventure in west Cornwall. The area, in general, is also one of my favourites for coasteering. The scenery is second-to-none, and there are also plenty of fine jumps in the area, too.

Final Thoughts

The video below is an accompanyment to this article. So, have a watch to see the run down of all the sea caves in Cornwall mentioned in this article.

Writing this post, I’m definitely excited to visit all of these caves once again, next time making sure I take a torch so I can explore every nook and cranny! Now that I’ve explored all of west Cornwall in Project Penwith, I’m also looking forward to coasteering further afield in Cornwall, and exploring some of those giant sea caves up the coast.

Having explored huge amounts of Cornwall’s coastline I firmly believe that Cornwall has some of the best coastal caves in the uk. Hopefully this glimpse into just a few from the far west gives you a sense of why I think so.

FAQs About Sea Caves

Here you will find answers to any other questions you may have sea caves in Cornwall and beyond.