After years of exploring Cornwall’s coasteering, this exploration culminated with the completion of ‘Project Penwith’ – we had finally completed exploring every section of coasteering-worthy coastline in west Cornwall, from the tame coasteering found in St. Ives Bay, all the way around the wild Penwith coastline, around Land’s End, and back towards Penzance. By this time our explorations had already taken us quite far past Penzance on the south coast of west Cornwall too.

From Project Penwith to Project Cornwall

Did that mean that our coastal explorations had finished? Certainly not! It’s a bold ambition, but Project Penwith has now evolved into Project Cornwall – would it be possible to coasteer the entire coastline of Cornwall? Well, why not?! Someone has to do it, and it may as well be me. It will probably take years, and I may never complete it, but I’m sure there’ll be many amazing adventures coasteering every nook and cranny of Cornwall’s tremendous coastline.

Can You Really Coasteer Every Part of Cornwall?

Well, no. As with Project Penwith, I didn’t do coasteering along every part of the coastline in west Cornwall. “Fraud!” I hear you cry. Wait a second. Not all coastline lends itself to coasteering, and therefore these areas can be discounted. An obvious example are sandy beaches. As anyone who has ever been for a swim at the beach instantly knows, wading along the sandy shore, or walking along the sand beneath the high tide mark is NOT coasteering. To claim otherwise would be ridiculous.To validate my claim, I have to therefore justify what I consider to be terrain that is, or is not, coasteering. These are my personal criteria, others may have different ideas, and there will be areas of coast that fall into decidedly grey area.

Simply donning a wetsuit, buoyancy aid, and a helmet, and getting in the sea doesn’t necessarily mean you are coasteering, in my opinion. Wikipedia describes coasteering as:

“A physical activity that encompasses movement along the intertidal zone of a rocky coastline on foot or by swimming, without the aid of boats, surf boards or other craft.”

I would broadly agree with this, but I think it’s also important to define the nature of the environment in which you are carrying out coasteering. Sadly, there are plenty of coasteering providers taking paying clients coasteering on coastline that barely qualifies as coasteering, in my book.

The culprits are often surf schools who have tagged coasteering on to the plethora of activities they offer. They know that coasteering is popular, and many of their participants have not been coasteering before, so won’t necessarily know that they have had a second-rate experience.

These providers often have no personal passion for coasteering, and little experience of coasteering beyond the one or two routes that they have set up shop on. Caveat emptor – buyer beware.

What Is Coasteering, Really?

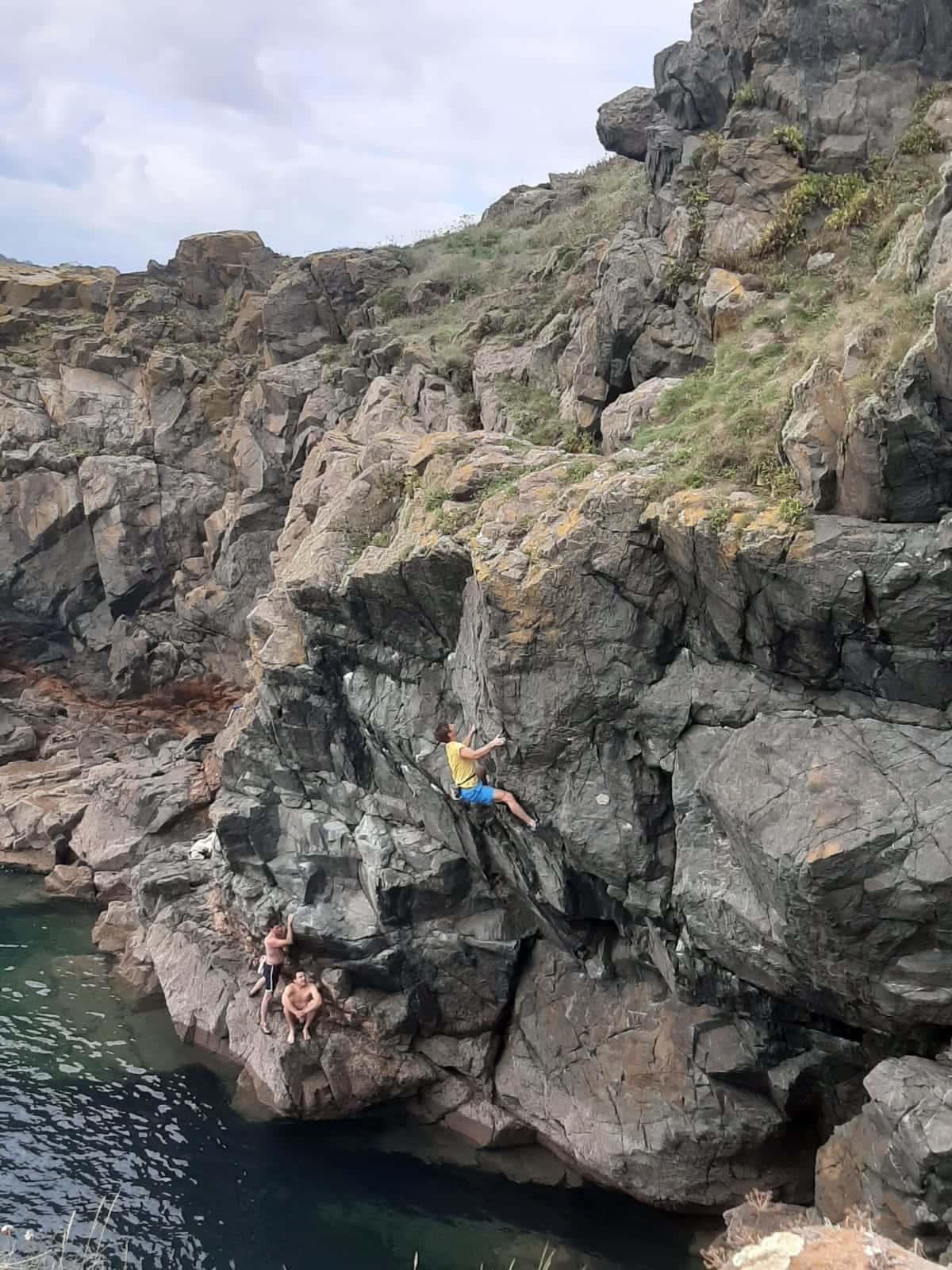

When you are coasteering, the majority of the time is spent either in the water, close to the rocks; or on exposed rocks, mostly below mean high water, or just above it. Only occasional forays well above the high tide are undertaken, usually with the purpose of finding jumps, or indulging in a spot of DWS (deep water soloing) – rock climbing above deep water, with the only means of safety being a crash into the water if you fluff it!

At the absolute extreme, one would generally find that coasteering takes place well within a boundary of 50 metres either side of the water line, whether that’s in the sea below it, or on the rocks above it. As stated, this is an extreme and for the most part, coasteering is almost entirely conducted within a few metres of the water line.

If you are coasteering and you are vaguely sensible, you’ll be wanting to use standard coasteering PPE (personal protective equipment), i.e., a wetsuit, helmet, buoyancy aid, and suitable footwear. In addition, at least one member of the coasteering party should be carrying emergency equipment, just in case.

Of course, the objective when coasteering is to move along a section of coast, so you will necessarily change modalities from swimming, pawing along submerged rocks, wading, scrambling, and if you’re lucky, an occasional bit of walking along an exposed ledge or reef. Too much walking though, and you’re possibly not coasteering any more (see below)!

What Isn’t Coasteering?

To define more clearly what coasteering is, it may be easier to explain what coasteering isn’t!

Sandy Beaches and Boulder Beaches

Beaches are not coasteering terrain, as stated above. This seems obvious when thinking of one of Cornwall’s gorgeous sandy beaches, like Sennen’s Whitesand Bay, or the 3-mile stretch of golden sand in St. Ives Bay. This colossal stretch of sand extends from Carbis Bay all the way to Godrevy. There’s clearly no coasteering to be done anywhere in between.

What may be less obvious are the huge stretches of boulder beach that occupy large sections of the coast. A good example of this is the expanse of boulder beach between Porth Nanven, near St. Just, all the way to Gwynver beach, near Sennen. This stretch of beach is also 3 miles long.

Short sections of boulder beach can be encountered when coasteering, and they are a necessary evil. They are awkward to traverse, whichever way you choose to do it. You either stay out of the water, wade awkwardly through the water, or go out to deep water and swim past the whole lot.

Neither option is much fun, and all three options put you on questionable ground as to whether you are actually coasteering. Thus, if boulder beaches are prolonged, they are best avoided, and I discount this terrain from that necessary to coasteer along.

Walking the Coast Path

Other sections of coast never seem to be underwater, even on the highest of tides. Large sections of Cornwall’s coast appear to be like this. There are long sections of coast where it is generally possible to walk at, or near, the high tide line, without resorting to getting wet, or regularly scrambling as you would be if stuck between sea and cliff.

Annoyingly, such sections of coastline may have occasional promontories jutting out into the water, which would mean the coasteering completionist would need to basically go for a long walk, only occasionally having to coasteer around a very short section of cliff, before repeating the process all over again.

And if you ever find yourself on an obvious path, you’re definitely not coasteering anymore!

Wild Swimming

Wild swimming is an activity that has gained immense popularity in the last ten years or so. Quite honestly, it’s broad appeal means that its popularity leaves coasteering the dust. It’s baffling to me, as I describe wild swimming as coasteering without the fun bits!

Coasteering is all about interacting with where the sea meets the land, and its hands-on and very tactile nature of exploration is what makes it so much fun. To remove these elements dilutes the activity until we can not call it coasteering anymore. Therefore, if you are in the sea consistently avoiding the rocks and swimming in deep water, you are wild swimming, not coasteering. Go somewhere else for that, that’s not what we do!

Rivers and Estuaries

Where the water turns brackish, the coastline will most likely turn to sand, or even mud. Unless you enjoy having your trainers getting sucked off by the mud with every footstep, or swimming through brown, muddy soup, you’ll probably agree that rivers and estuaries are not coasteering terrain. Therefore, the larger rivers and estuaries of Cornwall we can immediately discount, such as the Fal, Camel, and Tamar estuaries.

Man-Made Coastline

Another type of coastline we must consider is that which is man-made. This would include harbours, ports, sea defences, and so on. Firstly, the terrain found in these environments is unlikely to lend itself to coasteering, as we’d expect to find environments such as beach, boulders, or mud flats, which we have already discounted. Then there is also the obvious hazard of coasteering in a working industrial area, such as a busy port or harbour. No, it’s better to leave these places to the fishermen and other people using these sites for either their work or leisure.

There are many grey areas where the boundaries between what is considered coasteering and what is not blur together. For example, when exploring a wild section of coast, you invariably get some coves with sandy beaches or strewn with boulders. They are usually short-lived. Or occasionally you’ll get a large expanse of exposed reef, where the temptation to walk and make up some time cannot be ignored. But sooner or later, you’ll find yourself back to proper coasteering.The more troublesome areas are those which are, by and large, not coasteering, but have sporadic sections of coasteering that simply aren’t worth doing in their own right. I’ll have to make these calls as I go. I must admit, that much of the farther-flung coastline of Cornwall I really don’t know at all. But what I will state for sure, is that I will not be covering every centimetre of Cornwall’s coastline.

How Much Coastline Can Actually Be Coasteered?

Based on the criteria above, there are literally tens of miles of coast than we can discount in our bid of coasteering Cornwall in its entirety. The coastline of Cornwall is estimated to be 400 miles long. I’m not sure how this is measured. The coastal path in Cornwall is almost 300 miles long.

This distance is magnified many times when coasteering at sea level. The complex terrain, with all its twists and turns, caves, coves, and narrow zawns, means the true distance required to coasteer is immeasurable.However, the coastline of west Cornwall is estimated at 40 miles, and irrespective of how it’s measured, I have already done all of that. It does leave a staggering amount left to do. But it is conceivable, plugging away here and there.

Where Is the Best Coasteering in Cornwall?

Well, if I complete Project Cornwall, I’ll be supremely qualified to answer this question! And indeed, what makes ‘good’ coasteering? Some sections of coastline have the most fantastic scenery, but the coasteering is just not that good. Why? It’s difficult to put into words, but simply the experience you have traversing the coastline can be very different from one route to another.

A perfect coasteering route has just the right mix of elements, leading you to be fully immersed in all the good things about coasteering, from pawing along the rocks in the water, to good flowing scrambling. And when all this comes together, it is mixed with perfect elements of exploration, hopefully including some tasty jumps and some good sea caves to explore.

Knowing west Cornwall inside-out, I am of coursed biased. I do think it’s an amazing area for exploring the coastline by coasteering, and have had many adventures discovering its hidden secrets, whether it was with friends, colleagues, or on solo exploration missions. Whether it’s the stunning cliffs of Land’s End, our most popular guided route at Praa Sands, or the even more remote stretches, for example near Zennor or Gwennap Head.

But does west Cornwall have the best coasteering in Cornwall? Every time you explore a new section of coast, you usually find something that makes the visit worthwhile, even if it’s just one cave, jump, or other feature you discover. But there have been a few sessions that were distinctly underwhelming.

I can categorically say that Carbis Bay to Porthminster in St. Ives is the least exciting piece of coasteering in west Cornwall. Luckily, in west Cornwall at least, underwhelming coasteering is the exception, not the norm.I know that I will have to tackle sections of coast that I know will be underwhelming, just to get the job done, and so be it.

But on the whole, I’m very excited to keep searching the coastline. I love sea caves, and although some of the sea caves in west Cornwall are mind-blowing, I know they’re not the biggest in the county. Having already explored a few others, I know that the section of coast from Godrevy to Perranporth is home to some genuinely monstrous caves. What else is out there?

If you’re planning a trip to the South West, I recommend checking out Oliver’s Travels’ Cornwall guide which highlights the region’s adventures, accommodation, and essential visitor tips.

Coasteering Region by Region

Godrevy to Portreath

At the time of writing, we’ve coasteered from Godrevy to Fishing Cove. As we had some prior knowledge of this coast, we knew there were some incredible sea caves to be explored. Another feature of this coast is the proliferation of ancient mine workings encountered. Specifically, mine workings in the back of sea caves.

It seems that mine workings in sea caves are almost a uniquely Cornish phenomenon, and on several occasions, we have transitioned from coasteering to mine exploration and back again. As if some of these sea caves weren’t impressive enough in their own right, you may find an old portal high up in the back, that the miners would have reached by traversing precariously along a narrow ledge high above the sea. Truly bonkers stuff that has to be seen to be believed!

From Fishing Cove to Portreath, a good stretch of coasteering remains, but with planning and knowing the right entry and exit points, it can may be completed in 4 or 5 sessions.

Portreath to Perranporth

What lies beyond Portreath? The nature of the coastline here looks broadly similar to the Godrevy to Portreath section. So, we can expect more giant sea caves and brief skirmishes into old mines.

Along the way, we’ll have to continue coasteering around St. Agnes head, some of which we explored in the summer of 2021. Having rock climbed at Carn Gowla for many years, it was top of my list of places to explore outside of west Cornwall. With its towering, inescapable cliffs, and jaw-dropping caves, it certainly didn’t disappoint.

Also in that area is the area around Cligga Head. Home to the famous Cligga mine, I’ve heard and seen good things about the coasteering here, and the bizarre geology of the area will definitely offer up some beautiful and interesting coastline.

Coasteering Around Newquay

Newquay is undoubtedly Cornwall’s capital of coasteering, where a large number of providers guide clients of a couple of routes on the main headlands either side of Fistral Beach. But between Newquay and the long stretch of sandy beach at Perranporth, there are a few headlands that would have any coasteering explorer salivating. It’ll be nice to tackle these deserted stretches of coastline, just a few miles from all the chaos of coasteering in Newquay.

Newquay to Padstow

Beyond Newquay, my own knowledge of Cornwall’s coastline becomes a lot more sketchy. The miles of sandy-beach-meets-immediately-vertical-cliff around Watergate Bay may not require coasteering, but a more detailed recce is required to establish this.

If only for the iconic views, coasteering at Bedruthan Steps is a must-do, and I’ll make sure to have a drone pilot on hand for that one! Just around the corner from Padstow is Trevose Head. This looks epic, and there is talk of yet more massive caves. So, even if this stretch of coastline becomes more sporadic, there is plenty to look forward to.

Padstow to Bude

On the other side of the Camel estuary, the coasteering continues. Various providers run their activities in these areas, so when the time comes, I’ll be contacting them for the low-down on exploring these areas. The coastline around Polzeath, Port Isaac, and Tintagel, are all home to good coasteering terrain. I wonder if you can swim through Merlin’s Cave at high tide?

My visits to the far north coast of Cornwall almost entirely consist of rock-climbing trips. This is the start of the Culm Coast, and this distinctive sandstone is home to some amazing rock-climbing crags, such as Lower Sharpnose Point, and Vicarage Cliff. As an aside, the best cream tea I’ve ever had was up this way, after climbing at Oldwalls Point. If you’re ever in the area, make sure you go to the Rectory Farm Tearooms in Morwenstow. Those cream teas are a good reason to go there in their own right!

However, my impressions this coast are the ‘not quite covered at high tide’ category. Pebbly beaches go on and on, for miles, with maybe just the occasional headland jutting out into the sea. When I get the chance, I’ll have to nip up there for a recce and a cream tea, to find out just what needs to be coasteered, and what can be discounted.

Exploring the Lizard Peninsula

Next on our list on the south coast of Cornwall, is to explore the Lizard Peninsula. I have done some coasteering on the Lizard at a few locations, and it has been quite good. An overview looking at Google maps would indicate that the peninsula on the whole is a bit of a mixed bag.

In particular, the east coast of the Lizard looks like it might be home to some poor coasteering. Being relatively sheltered, it seems this coast hasn’t suffered the full battering that Cornwall’s north coast has endured, and it is that battering that has led to formation of its formidable cliffs and resulting good coasteering.

Nonetheless, I have faith that there are plenty of good sections to explore starting around Church Cove and Mullion, rounding Lizard Point before the coastline finally mellows out upon transitioning into the Helford estuary.The photgraph below shows Loe Bar beach at Porthleven. These huge waves occurred during Storm Fanklin in Febraury, 2022, obviously not a time of place for going coasteering!

Loe Bar marks the start of the Lizard Peninsula, and it’s sandy beach extends for miles. This means we don’t have to resume our coasteering explorations until it peters out into rocky terrain near Church Cove, Gunwalloe, and Mullion.

South Cornwall – The Roseland to Rame Head

My lack of knowledge of this coastline and my general impressions are that the coasteering from the Roseland to Rame Head and Torpoint may well be quite sporadic. But that hopefully means there are some real gems to be found along that section.

I have only been to Rame Head once, and that was in the middle of the night to do some astrophotography (see photo below)! One thing is very noticeable about coasteering in south Cornwall: there is a real dearth of coasteering providers offering guided coasteering in this area.

With popular holiday resorts like Fowey, Looe, and Mevagissey, there’s no shortage of visitors to this part of Cornwall. Is this due to a lack of good coasteering, or some other reason? There’s only one way to find out…

Stay tuned for blogs and videos as we document our journey coasteering around Cornwall (and beyond!).