Coasteering the Whole of Cornwall Continues

In this episode we explored the coasteering around Porthleven in west Cornwall. This is part of our ongoing mission to explore all of Cornwall’s coast by coasteering.

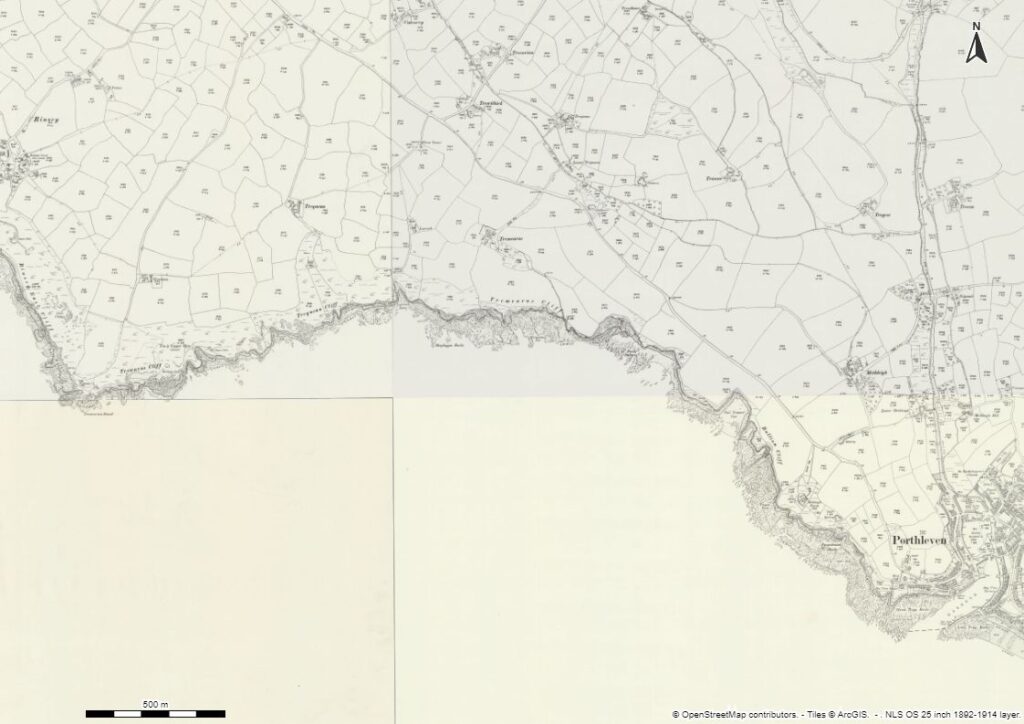

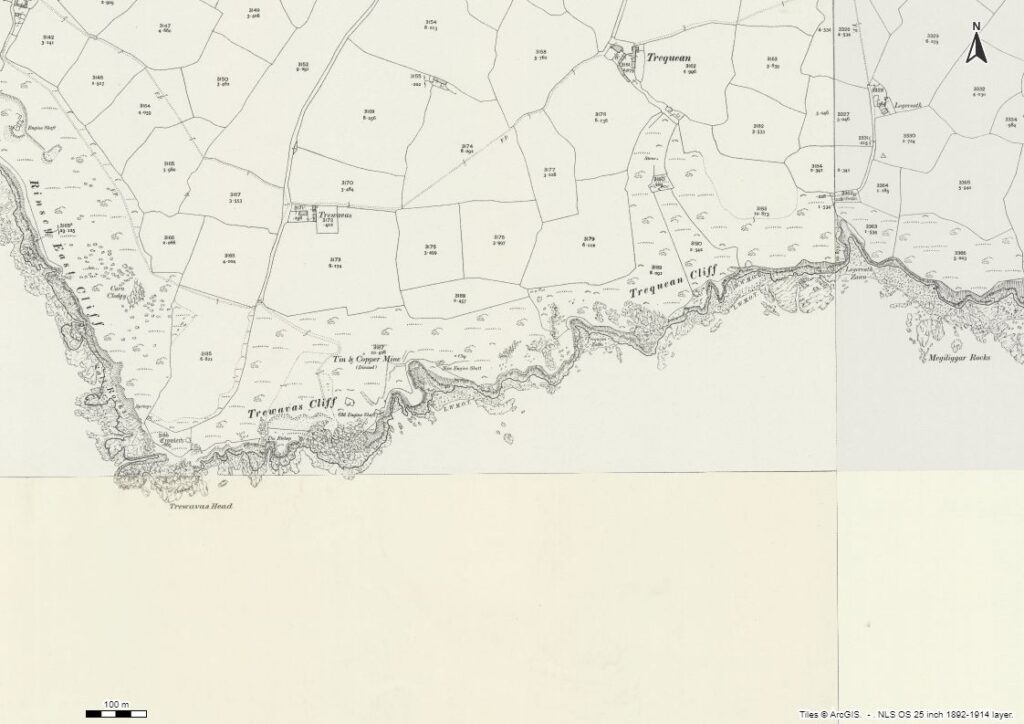

Where: Trewavas Cliff to Porthleven, Cornwall

How: Coasteering

When: April 24, 2023

After completing coasteering the whole of the Penwith peninsula in west Cornwall, we have started working our way up both the north and south coasts of Cornwall. It’s a bold statement, but I intend to coasteer and sea-level traverse the entirety of Cornwall’s coastline.

On April 24th, 2023, I set off with Jamie to continue our coasteering of Cornwall’s south coast. Previous exploration had taken us from Rinsey Head, near Praa Sands, all the way to Trewavas Cliffs. This was the next section of coastline heading eastward from our coasteering route at Praa Sands, where we run most of our guided sessions for coasteering in Cornwall.

The section Coasteering from Rinsey Head to Trewavas Cliffs. This was a wonderful explore, taking in the gorgeous granite coastline around Rinsey Head and Porth Cew.

The particular highlights were the wonderful sea caves going through Rinsey Head, not to mention exploring the abandoned mine workings of Wheal Trewavas. Cornwall must be one of the few places in the world where it’s often possible to transition from coasteering to mine exploration in the same adventure. Go here to see the video of that particular coasteer.

Coasteering from Trewavas Cliff to Porthleven

But back to today’s explore. Our first challenge was to find the top of the zawn that we could descend to sea level to start coasteering. Finding the zawn was no problem, but penetrating the natural barricade created by thick hawthorn was another matter. Luckly, 5mm wetsuits make pretty good armour against even the spikiest vegetation.

After scrambling down the steep zawn, we marvelled at the wonderful formations in the granite cliffs. We also speculated at the rock-climbing potential here. Whilst climbing of the upper cliffs around Trewavas Head is well known, very little development is recorded on the sea-level cliffs.

Lo and behold, as we were weighing up the viability of a particular line of the rock face, Jamie spotted a rusty old piton – the relic from a historic, and unrecorded ascent.

We traversed the large, rounded, granite boulders until we were finally compelled to enter the water. Immediately we were in stunning surroundings with the towering granite cliffs looming above us. There’s something about the granite cliffs of west Cornwall, they’re so aesthetically pleasing, compared to the other rock types in Cornwall (mostly killas slate).

As an aside, it’s just one thing that makes our coasteering at Land’s End so epic.

Sea Caves – One of the Best Things About Coasteering

I have spent so much time climbing on the popular crag of Trewavas above, but I’d never been able to see this area from sea level. Now, at last, we were coasteering here. Straight away we discovered some excellent sea caves.

Sea cave exploration really is, at least for me, one of the very best things about coasteering. These other-worldly places are simultaneously fascinating, as well as a little scary. It really does feel quite unnatural to venture into the darkness up to your neck in water.

We coasteered into two reasonably large caves, and then discovered a third. This sea cave was not very deep, but had a pillar at its entrance, effectively creating a double entrance. You could therefore thread in one side and come out of the other.

It’s just a small example of the endless creativity of nature to make wonderful forms for us to enjoy exploring.

Coasteering vs. Sea Kayaking?

At that time, a fleet of sea kayakers came by. They turned out to be members of Penzance Canoe Club, some of whom I know. It was great to see them out enjoying this calm April day, also.

Off they went, leaving us to continue our coasteering expedition. Why explore the coastline by coasteering when you can cover so much more distance in a kayak?

It’s, of course, a completely personal choice. For me, I simply love the totally hands-on way of exploring and interacting with the environment that comes with coasteering. Not to mention you have almost no limit to the spaces you can access, unencumbered by a large craft.

So as the kayakers soon disappeared, there was no disputing that they would reach Porthleven hours before us. But I’d like to think they didn’t explore in anywhere near as much detail, or indeed have as much fun…

Trequean Cliffs – Where Granite Meets Slate

Directly underneath the East Crag of Trewavas lies Trequean Zawn. This zawn is a large boulder-strewn cove. It has a tiny pinnacle, almost a little sea stack. However, even at the highest tides it is never completely cut off from the mainland.

We snuck around its narrow neck, in a move something akin to threading Nape’s Needle on Great Gable in the Lake District and continued around the corner, in an area known as Trequean Cliff.

Around the corner we were immediately greeted with a monster of a sea cave. Around the headland, the granite cliffs became very sheer, and a mental note was made to return here to investigate its potential for some hard trad climbing or deep-water soloing.

This sheer wall culminated in a beautiful cave. It was relatively narrow, but maybe as much as 20 metres high. We gently rode the swell into this granite cathedral. As with the previous caves we’d found, it wasn’t hugely deep, just a few tens of metres in depth. Good enough for me.

As a graduate of Camborne School of Mines and having done a little bit of geology fieldwork in west Cornwall in my younger days, I knew that we were soon going to be meeting the contact where the granite meets the killas slate.

Thus this geology contact point, which may have been of little interest, or even unnoticed by some, marked a significant waymark in our exploration of this coast. Beyond this contact, there is no more granite to be found for the remainder of the south coast of Cornwall.

As we walked along an exposed reef, the contact was clearly visible. Beyond this point the cliffs change their nature immediately, being of killas slate. Killas slate is a low-grade slate that was deposited nearly 400 million years ago.

It is very often very friable, and weathers in a much more angular way than granite, as erosion exploits its jagged cleavage plains.

It’s also in the killas that it seems Cornwall’s longest sea caves tend to form. Would there be any huge caves waiting for us between Trequean Cliff and Porthleven?

Megiliggar Rocks – Cornwall’s Geological Layer Cake

Megiliggar Rocks was our next stop. This area is of geological significance, as the location of some gigantic granitic sheets, which extend outwards from the granite into the killas slate. The result is a giant geological layer cake, with thick, cream-coloured sheets punctuating the grey-brown slate.

Megiliggar Rocks was a regular fieldwork location for geology students. However, its only path giving access from above, collapsed a few years ago. That means unless you’re willing to coasteer or kayak to Megiliggar Rocks, fieldwork opportunities here are now extremely limited.

From here, we were pretty much on dry land for a fair way. In fact, we had chosen to do this stretch of coastline at low tide. For much of this section of coast we didn’t actually anticipate much quality coasteering.

But there were certainly going to be long stretches of flat ledges. It was going to be much easier to simply walk across these at low tide than have to swim, wade, and fumble our way across them at high tide.

Tortured piles and pinnacles of killas decorated the cliffs as we ventured on to Tremearne Par beach. Being halfway between Rinsey Cove and Porthleven, this is a relatively isolated beach. Whilst by no means one of the prettier beaches in west Cornwall, anyone seeking a spot away from the crowds will be well-rewarded.

The Coasteering Continues

The promontory that separated Tremearne Par from the next cove steepened up and we were gladdened when the ledge-walking stopped and the ‘proper’ coasteering resumed. This short section of coast provided all of the features you’d expect from a good coasteering route.

Steep cliffs, but with accessible ledges and traverses, interspersed with some little zawns that offered a handful of reasonable cliff jumps. It was short-lived, but very good stuff.

As we turned the corner and headed into Nicholls Cove, we came across that other crucial ingredient for a good coasteer – another sea cave. This cave had an ominous feel and gave the impression that it was potentially quite long. We proceeded to swim inside.

Our first assessment was confirmed, it was a long one. But what made what is ordinarily a bizarre experience quite a lot worse, was the fact that this cave was full of rotting seaweed! Of course, it stank, and it was genuinely unpleasant having to swim through the stuff in near-darkness.

But, it certainly wasn’t a good enough reason not to explore the cave, so we ventured on. It had a stub going leftwards that didn’t go far, but the right-hand continuation went back a fair way.

It maybe was only about 50 metres in length in total. That doesn’t sound far on paper, but it’s far enough to be nearly pitch black and seems a long way when swimming in the dark.

We emerged from the cave and negotiated a narrow gully that delivered us to Nicholls Cove. Known as Porth Sulinces on the older maps, it at some point acquired its modern name.

Nicholls Cove and Methleigh Mine

Nicholls Cove is a large, golden sandy beach, surrounded by towering cliffs of fragile killas. There’s no way to access the cove safely from above. If there was, it’d be one of the more popular beaches in west Cornwall. What made this stunning place all the more special, was the fact that we had it completely to ourselves.

It even appeared that the kayak party we had met earlier hadn’t stopped here, as the only footprints in the sand were our own.

We made a small diversion to investigate some holes in the cliff in the centre of the beach. Our first thoughts were immediately confirmed – these were old mine workings. Some awkward scrambling allowed us to gain access to these adits.

I set about exploring the first tunnel which, strangely enough, was parallel to the main cliff face, going into a slight promontory. This adit didn’t go very far, so with that one ticked off, we looked into the next one. This adit went straight inland, deep into the cliff.

A tricky climb gained the adit entrance and I had to get on all fours to enter the tunnel. I was immediately met with deep, orange, iron-rich mud. The only way on would have been to crawl through this ochre-stained horror show. It was outside of the scope of our objective for the day, so we withdrew, leaving that one for ‘another time’.

During a later discussion with my colleague, Ben, at Cornwall Underground Adventures, he said it was most likely the ancient Methleigh mine. The name was familiar, with Methleigh Farm being a site nearby were my friends and I had previously had a private bouldering wall.

Parc Trammel Cove and Zawn Shagg

We left Nicholl’s Cove and started coasteering along the vertical cliffs that bounded the eastern end of the bay. As we rounded the corner, we were greeted with yet another cave. Great stuff!

We ventured in and quickly realised this was actually a through cave. Through caves are always such pleasing features, as if these natural tunnels were made for us to explore. We journeyed through, with a mixture of swimming and pawing along the walls, enjoying being jostled by the slight swell pulsing through the cave.

The cave delivered us into Parc Trammel Cove. Like Nicholl’s Cove’s younger brother, this was another pristine sandy cove, albeit smaller. But with cliffs equally as steep and foreboding, it had a very dramatic feel. It was just us and the many seabirds that had made their nests on ledges on the fragile cliffs above.

A promontory of steep killas separated Parc Trammel from Zawn Shagg next door. This provided some brief opportunities for some climbing and jumping from its jagged ledges. We had arrived at Zawn Shagg.

Lacking the sandy beaches of the former two coves, Zawn Shagg was much smaller, but certainly no less steep-sided. It had two caves in its back that were not well-developed. So, rather than coasteer all the way to the back, we decide to press on and continue coasteering to Porthleven.

Finishing Coasteering to Porthleven

Much of the remainder of the journey was made easy by almost continuous, flat, exposed wave-cut platform. We passed under Bullion Cliff and rounded Tregear Point, where a couple of fishermen were trying their luck fishing off the reef.

The next stretch of reef is called Pargodonnel Rocks. Care had to be taken on the slippery, seaweed-covered ledges, and we were rewarded with a final, small sea cave.

Right at the end of the journey, we crossed the tautologically-named Zawn Cove, which now has a British flag waving above it. It seemed it had been hoisted specifically in our honour, as we climbed onto the rocks and got our first full view of Porthleven, with its quaint little harbour.

We had all but done it, with just a hundred metres or so to cover until we reached the edge of the harbour. We simply had to cross Great Trigg Rocks. Known today simply as Porthleven main reef, this area of flat rocks provides on of the southwest UK’s best surf breaks.

Luckily, there was no swell today, so it was no problem to traverse this often-treacherous slab of rock. And with that, we were in Porthleven. We had coasteered a pretty long section of coastline. But our strategy of tackling it at low tide had meant it only took us 5 hours.

Another stretch of the Cornish coast had been completed. And it was a significant one. Porthleven unquestionably marked the end of the coasteering on the south coast of west Cornwall. There is no ambiguity, as east of Porthleven, the uninterrupted sand of Loe Bar Beach continues for many miles, until the rocky coastline resumes on the Lizard peninsula.

Whilst I have done a smattering of coasteering on the Lizard before, I am certainly looking forward to exploring it thoroughly. I have no doubt that sections of it will yield some top-quality coasteering.