Exploring The South West Coast Path in West Penwith from Sea Level

West Penwith is Cornwall’s most westerly district, stretching from the Hayle Estuary on its north coast, to just beyond Marazion on the south coast. Here you’ll also find some of the best beaches in Cornwall, such as Sennen Cove and Nanjizal, as well as hidden gems like Porthmeor Cove and Portheras. The region also features some of Cornwall’s most iconic coastal landmarks, such as the Crowns engine house at Botallack Mine, or the historic fishing villages of Porthgwarra and Penberth.

As measured by the Southwest coast path, West Penwith consists of 50 miles of beaches, cliffs and scattered boulders. In 2020, Kernow Coasteering founder, Matt, completed his personal quest to coasteer every part of the West Cornwall Between St. Ives, Penzance, and beyond. This took place over many years, and using the West Cornwall coastal path as a parallel, Matt describes how exploring every nook and cranny of the West Penwith coastline came to be.

Note that only those with a high level of experience should go coasteering without a guide. So folks, don’t try this at home! If you are keen to try coasteering in Cornwall, then you’re in the right place — head over to our main coasteering page to find more about our guided coasteering adventures.

Botallack Mine: The Final Stage of Project Penwith

In spring of 2020, ‘Project Penwith’ quietly came to its conclusion. As I ascended the crumbling cliff to rejoin Cornwall’s coastal path at the iconic engine houses at Botallack Mine, I had reached the finishing line of a journey that began seven years earlier. That journey was coasteering every ‘coasteerable’ section of coastline from St. Ives, heading west towards Sennen Cove and Land’s End, and continuing along the south coast of West Cornwall, beyond Penzance to the home of our guided coasteering routes at Praa Sands.

Whilst I have walked the entire South West Coast Path of West Cornwall in a single (very long) day, Project Penwith was many years in the making, chipping away at each individual section when time and weather conditions allowed.

Those not familiar with coasteering, and just what level of detail you cover the coastline in when doing it, would not be able to grasp the amount of coastline covered. Even though you’re never that far away from the coast path when you’re coasteering, the experience is very different. It’s arduous, physically demanding, and the extremely complex nature of the coastline greatly increases the amount of time it takes to traverse it.

Coasteering All of West Cornwall — The Rules

My rule when exploring the coast by coasteering is simple: I must be never more than fifty metres from the water’s egde, in either direction at any time. On the one hand, that prevents huge power swims that avoiding interacting with the coast. On the other hand, it prevents straying too far from the inter-tidal zone where, by defintion coasteering takes place. Additionally, you must never find yourself on the coast path as that would definitely mean that you’re not coasteering any more!

Depsite this, my aim was not to traverse every inch of the West Penwith coastline, but to only traverse the sections that mostly consisted of coasteering in its recognisable form. Thus, I didn’t include the huge sections of beach, like the miles long Marazion Beach or the 3 miles of boulder beach stretching from Porth Nanven to Gwynver beach, near Sennen Cove.

Similar terrain excluded shorter sections, such as immediately west of Porthmeor beach, at St. Ives, until the real coasteering starts at Clodgy Point. On the south of the peninsula, the long stretch of boulder beach at St. Loy, east of Penberth Cove, also offers nothing in the way of coasteering. That leaves an awful lot of coasteering on the remaining cliffs, years’ worth, in fact…

Early Explorations at Porthgwarra and Pendeen

Like many things in life, Project Penwith started by accident. The first sections were discovered and explored back in 2012, whilst I was searching for routes for what was to become Kernow Coasteering. Those initial explorations revealed some early gems, including routes we still use with our customers to this day, such as at Pendeen Lighthouse.

I do remember on a winter’s day, assembling with some mates in the car park at Porthgwarra, as a light snow was falling, to go and explore the coastline around Gwennap Head. To date, it’s the only time that I have been coasteering in snow.

Descending the cliffs at Carn Guthensbras led to a committing start, with a sizeable jump to get things started. As we headed along the coast towards the tiny beach of Porthgwarra, given its moment of fame as Ross Poldark’s bathing spot of choice, a good chunk of coastline had been explored. The scenery was undeniably stunning, but the quality of coasteering wasn’t the best, so the route wasn’t developed.

West Cornwall is particularly exposed to swell coming in from the Atlantic, relative to the rest of Cornwall. This has been instrumental in shaping the stunning coastline here, but does create problems for coasteering. Those of you who have been coasteering with us on a rough day at Praa Sands, will know exactly what I mean!

A memorable early exploration was seeking an answer to this problem. Facing east, and therefore potentially offering some shelter from winds and swell, a friend and I set out one stormy day to coasteer the stretch of coast from Kemyel Point, near Lamorna, back towards Mousehole. The hope was to find a route that offered shelter from those westerlies, similar to those lucky folks up at Newquay, who can coasteer at the Gazzle in almost any weather.

Alas, we bit off rather more than we could chew, and it turns out that that location offers no noticeable shelter from the Atlantic swells whatsoever! A very challenging but fun coasteering session ensued, as we battled the swells all the way back to Mousehole. It wasn’t a bad route, but it’s lack of jumps, caves and convenient exit points, not to mention its complete lack of shelter from the swell, meant that no further research was undertaken at the site.

The headland of Land’s End was explored back at this time too. It remains one of my favourite places to coasteer in west Cornwall. It has a few tasty jumps, so long as you hit them at the right stage of the tide, but what makes this route so special is its very committing nature, the quality of the cliff scenery, and the caves…So many caves, from cathedralesque caverns, down to the claustrophobic grotto we lovingly refer to as the ‘Ghost Train’.

We finally figured out a way in which we could safely offer the Land’s End route to our guests, and we now offer the Advanced Coasteer’ at Land’s End.

Coasteering: The Ultimate Way To Explore West Cornwall

As time went by, a desire to find more coasteering routes to share with our guests, gave way to a more personal interest in coasteering the whole peninsula. It was also a personal achievement, as I suspect no one else has ever traversed West Penwith at sea level.

And let’s not forget indulging the simple love of coasteering and exploring the coast — that was the primary motivation. I simply love the feeling of getting out there and exploring the coastline. It’s suitably remote to give one a feeling of genuine exploration, without having to go to the Himalayas.

It’s also an amazing way to connect with your local area. Living on a small peninsula in west Cornwall, and being interested in the outdoors, it is a no-brainer, at least for me, that I should get out there and explore the coastline. What genuinely surprises me is that no one else is doing it! You have to make the most of what’s around you, so that’s what I try and do. As well as coasteering, I am passionate about rock climbing and mine exploration, again things that West Cornwall offers in abundance.

Coasteering, for many people, will always be about the cliff jumping. Whilst I certainly like to indulge myself, it is the feeling of exploration that I enjoy the most. Even on routes I am very familiar with, or routes that I work on very regularly, it always feels like exploration to me. There is always something new to see, or a new way in which to see it, as weather and sea conditions are never exactly the same twice.

However, the feeling of exploring a new section of coastline is another level. Having literally no idea of what’s around the corner, whether it’s a jaw-dropping cave system, or a challenging swell feature that needs to be negotiated, is a very rewarding experience.

As mentioned above, no one is doing this. Who knows how many caves I have visited, and gullies and cracks I’ve squeezed through that, in all likelihood, no other human being has ever been in before? And, rest assured, any tasty jumps encountered along the way were definitely dealt with.

Piecing The West Cornwall Coastline Together

As the idea to coasteer the entire West Cornwall peninsula took shape, it was necessary to apply some logic to how it could be approached, and to cut down the coastline into chunks that could be realistically achieved in a single push. This would often be to link up to obvious landmarks, such as two headlands, typified by the very remote bay and headland coastline around Zennor.

Many of these coasteering sessions were undertaken with my fellow guides at Kernow Coasteering, as well as with friends. However, I number of the legs were done solo. I actually found some of these sessions the most rewarding, it certainly is much more adventurous going out into unknown territory by yourself.

This began in instances when the conditions were too good to miss, but no one was available. But, as time wore on, I started to acquire a taste for solo coasteering. Whether or not coasteering alone is a good idea, is a topic for another post.

All in all, West Penwith was explored in twenty-five individual sections of coasteering. Most of these could be tackled with about three hours of coasteering, not including walking. That became the optimal length, and it’s possible to cover a fair distance during that time. Any longer than that, and fatigue tends to get the better of you.

Marazion Beach to Sennen Beach: The South Coast

It was inevitable that the south coast would be completed first, being significantly more sheltered from swell and prevailing winds than the north coast. On any given day, the chances of getting out on the south coast are far greater than being able to access the north. The south coast was all but completed when most of the north coast remained unexplored.

Moving clockwise around the Penwith coastline, from Marazion Beach, heading west, I’d say on the whole the coasteering here is maybe the most patchy and discontinuous in the district. Despite this, there are one or two sections that rank extremely highly when measured against the other routes of the area.

For example, at Tater Du, just west of Lamorna, it is possible to coasteer along several different rock types, find inexplicably circuitous caves, as well as find something which can be a rarity in coasteering: huge jumps with deep water at low tide! The only other place I know that is as great coasteering at low tide is the route we use on the Isles of Scilly, at Peninnis Head.

After another long stretch of boulders around St Loy Cove, coasteering terrain reappears between Penberth and Porthgwarra. However, despite some of the most beautiful cliff scenery in the whole of Cornwall (not to mention some of the best beaches in Cornwall), the quality of coasteering doesn’t really ramp up until beyond Porthgwarra.

Almost all of the coastline between Porthgwarra and Sennen Cove is awesome — truly top-shelf stuff. I’m particularly fond of the granite coast of west Cornwall, with its golden, castellated crags forming particularly beautiful cliffs and features. The granite, in general, seems to lead to the formation of the larger sea caves in the area, which is always a huge tick in the ‘what-makes-an-awesome-coasteering-route’ box.

Cape Cornwall, Portheras, and Zennor: Penwith’s North Coast

Coasteering on the north coast of West Cornwall resumes at Cape Cornwall, and continues all the way to St Ives, taking in stunning, lesser-known locations, like Portheras, Porthmeor Cove, as well as the particularly remote coast around Zennor.

It’s propensity for rough conditions means that for much of the time from autumn to spring the West Cornwall’s north coast remains totally inaccessible. It was in the downtime between the first lockdown of 2020, and the start of that summer season that huge chunks of West Penwith’s north coast were explored.

The weather was unusually settled for a prolonged period which, combined with small swells, meant it was optimal time for north coast exploration. It was this period, coasteering in the strange times of 2020, that allowed Project Penwith to be concluded, possibly years sooner than it otherwise might have been.

The other factor that had marked much of the north coast as ‘low priority’ was its remoteness. With the coastline being very far from the road, especially between around Zennor, the huge walk-ins and walk-outs were not very appealing. These walk-ins were up to an hour in some cases, which may not sound like much, but in full coasteering kit, and on either end of a tiring three-hour coasteering session, they certainly felt like a lot at the time!

Conveniently, that was often the length of time needed to coasteer between the major landmarks that seemed the obvious places to divide the individual sections of coast. This particularly holds true for the north coast of Penwith, with the major headlands of Clodgy point, Pen Enys Point, and Carn Naun Point, all being about three hours of focused coasteering apart from each other.

The most demanding section on the north coast was undertaking a very long stretch of coastline, from Portheras Beach at Pendeen, heading east to reach the nearest known safe exit at Porthmoina Cove, beneath Carn Galver.

This took a remarkable five hours in the water. I vividly remember the staggering scenery of Porthmoina Cove, with the high granite cliffs of Bosigran main cliff and Bosigran Ridge on either side. However, I also remember being so fatigued by that point, that I could barely swim, and my interest in the outstanding scenery was minimal. Needless to say, I have returned to what is some of the most impressive coastline in west Cornwall since that, to enjoy it in a more manageable chunk.

Come On, Where’s the Best Coasteering in West Cornwall?

Where do I begin?! Only a small handful of these individual sections of coast explored came up short, with few jumps or other interesting coasteering features, such as good caves and gullies to explore. So, I can say, hand on heart, that most of the coastline of west Cornwall offers amazing coasteering. Some of the sections I have returned to many times. Some I hope to return to and repeat again. As described above, it’s often those sections up around Zennor and St. Ives that I have yet to repeat, due to their remoteness.

I would love to share some of these routes with our Kernow Coasteering guests, but in all honesty, most of the sections are too remote, rarely calm enough, and require coasteering for a lot longer than the average group can comfortably handle. So, know that when you come coasteering with us, the routes we have chosen, have been carefully selected to get the right balance of awesome coasteering, as well as not being a back-breaking walk in. And that’s also why we have a number of routes that we use, to try and make the best of the volatile Atlantic sea conditions.

It’s fair to say that every section of the coastline is unique. Probably each section of coast has some unique feature that makes it standout. Whether it’s the giant caves bewteen Porthgwarra and Land’s End, the spitting backwash caves around Pendeen and the Tin Coast, or the precipitous zawns around the secluded north coast near Zennor, each section offered up something memorable. And, of course, the experience made all the difference, whether it was having a great trip out with friends, or taking on an isolated trip alone, in perfect conditions.

Whilst being a bit patchy at times, the killas slate coastline of the Tin Coast, from Cape Cornwall to Pendeen, taking in Botallack Mine, does have some amazing stuff. If coasteering here at low tide, the crazy pink seaweeds make a psychedelic contrast to the heavily mineralised rock, which can cover the full gambit of colours from black to bright green. This coastline is characterised by steep narrow zawns. Some of these are claustrophobic squeezes, whilst some are towering behemoths that leave one totally gob-smacked.

We do utilise this stretch, when swell conditions allow, to coasteer at Pendeen Watch. It’s an awesome route, that has a bit of everything mentioned above. Not only that, wide open to the Atlantic swell, it is often a bumpy ride, so hang on to your hats when coasteering here!

As we head east, towards Zennor St. Ives, we enter very far-flung terrain. The coast becomes further and further from the B3306, the West Cornwall Coast Road. This is where the walk-ins along the Cornwall coastal path start to become brutal, and would weed out all but the keenest coastal explorers. Furthermore, ways to easily access the coastline, or maybe more importantly, to escape, become ever more scant. Only with a detailed local knowledge of this coastline should one try and coasteer in this area of Cornwall.

I’d sub-divide this stretch of coastline into two sections. We’re back in granite for much of the way between Portheras Cove and Porthmeor Cove. With its northerly aspect, it differs subtly from the granite coastline of the west and south of the peninsula. Often shady, and often rough, it’s definitely a step further in terms of its isolation. It does include some of the most stunning cliff architecture, dare I say, in the whole of Cornwall. Not to mention some of the largest zawns and deepest caves. Some of these areas I’ve enjoyed visiting several times, and I’d like to re-visit the entire lot when time allows.

The remaining coast takes one from Porthmeor Cove to Porthmeor Beach. I promise that’s not a typo! One of those is in the middle of nowhere, just west of Zennor, the other is smack-bang in the middle of St. Ives. This is a long, lonely section of coast, and was tackled in a number of segments. Much of this was tackled in quick succession during the spring of 2020.

I have fond memories of these coasteering sessions, out in the middle of nowhere exploring the remotest terrain west Cornwall has to offer. This area offers a potpourri of incredible landscapes, filled with interesting caves, zawns, gullies and other features. Some of my favourite coasteering experiences ever have been exploring these sections by solo coasteering, and I have included one of them in the video below.

Coasteering The Edges of West Penwith

As I finished the final section, starting at the end of the Kenidjack Valley, and topping out at Botallack Mine, once again alone, Project Penwith quietly came to its conclusion. I had successfully coasteered the entirety of west Cornwall. Additionally, sections have been explored further east on both coasts. Continuing from St. Ives, there is a small section of rocky coastline between Porthminster Beach and Carbis Bay.

I initially checked this area out hoping to find an area sheltered from those westerly swells. Unlike the ill-fated expedition at Mousehole, this part of the coast does offer shelter in all but the stormiest of conditions. In fact, during winter storms, when every other beach is too big to surf at, you may find a few surfers here, making the most of a rare, but well-formed wave.

Coasteering here helped consolidate my hypothesis that exposure to swell is a double-edged sword. It can be a real pain in the neck when you are actually trying to coasteer. However, I think it may well be a necessary factor to form a good coasteering route. Only a coastline that has been exposed to large swells and storms over the aeons will form steep cliffs, chock full of great coasteering features, as waves have eroded cracks and other weaknesses to form the requisite caves, gullies and zawns.

A sheltered coastline, that is safe from centuries of battering by storms will remain a quiet and less dramatic place. Case in point at Carbis Bay. There is no worthwhile coasteering here. The route is very short, with no jumps above 4, maybe 5 metres, at a push. And that’s if you time it right on high tide. Sadly, this deficit in jumping is not made up for with a nice share of caves or gully features to enjoy. Still, as it’s there, it was necessary to go and have a look.

On the south coast, there is a large gap on the coasteering map inn Mounts Bay, from Mousehole, around Newlyn, Penzance and across Marazion Beach. The craggy coastline doesn’t reappear until you head east out of Perranuthnoe. And once the cliffs reappear, they immediately offer quality terrain. With relative shelter, compared to the north coast, it’s in these areas that we provide many of our guided coasteering experiences, so you will be able to see this for yourself when you come coasteering with us.

So far, I have pushed to coasteering almost to Porthleven. There is some fantastic, if patchy, coasteering in this area. One more session will take us coasteering into Porthleven harbour, beyond which is the lengthy Loe Bar. An infamously dangerous shingle beach, 2.5 miles in length, it signals the end of coasteering until reaching the Lizard Peninsula.

Coasteering All of Cornwall?

So, what comes next? I’m not sure I’m up for ‘Project Cornwall’, but as I didn’t set out to do Project Penwith, who knows?! I’m sure coasteering and entire county would be a world first, but with over 400 miles of coastline (who knows how much that would multiply to when coasteered?), and some real logistical challenges of coasteering at the other end of the county, please don’t hold your breath!

The mini-coasteer at Carbis Bay marks the end of coasteerable terrain for most of St. Ives Bay. The miles of golden sand from Hayle river mouth to Godrevy lighthouse provide endless enjoyment for surfers and beach-goers, but nothing in the way of coasteering. Well, that’s about 9 miles of Cornwall’s coastline discounted immediately!

The foreshore around Godrevy offers a potential fun mini-coasteer. I know this coastline well from bouldering. It is one of Cornwall’s premier bouldering locations, with home to hundreds of problems in its alley-like gullies. It certainly would offer very little in the way of jumps, but negotiating its maze of gullies on a high tide, with a little bit of swell, would be great fun, I’m sure.

Beyond Godrevy, there does look to be a mouth-watering stretch of coastline, comprised of steep cliffs and huge caves. With numerous localities here being popular seal haul-out sites, choosing when to visit would be paramount. It’s also a fascinating history in terms of its mining heritage. Innumerable adits and mine workings pock the cliffs in this area, being the northern extremity of one of Cornwall’s principal mining districts during the 18th and 19th centuries.

It’s seems realistic to think it’s possible to slowly explore the coastline all the way up to Newquay where, of course, coasteering was first unleashed on the public in Cornwall. See this blog post on the history of coasteering, including its development in Cornwall. I’d be particularly excited to coasteer the section around Carn Gowla, near St. Agnes.

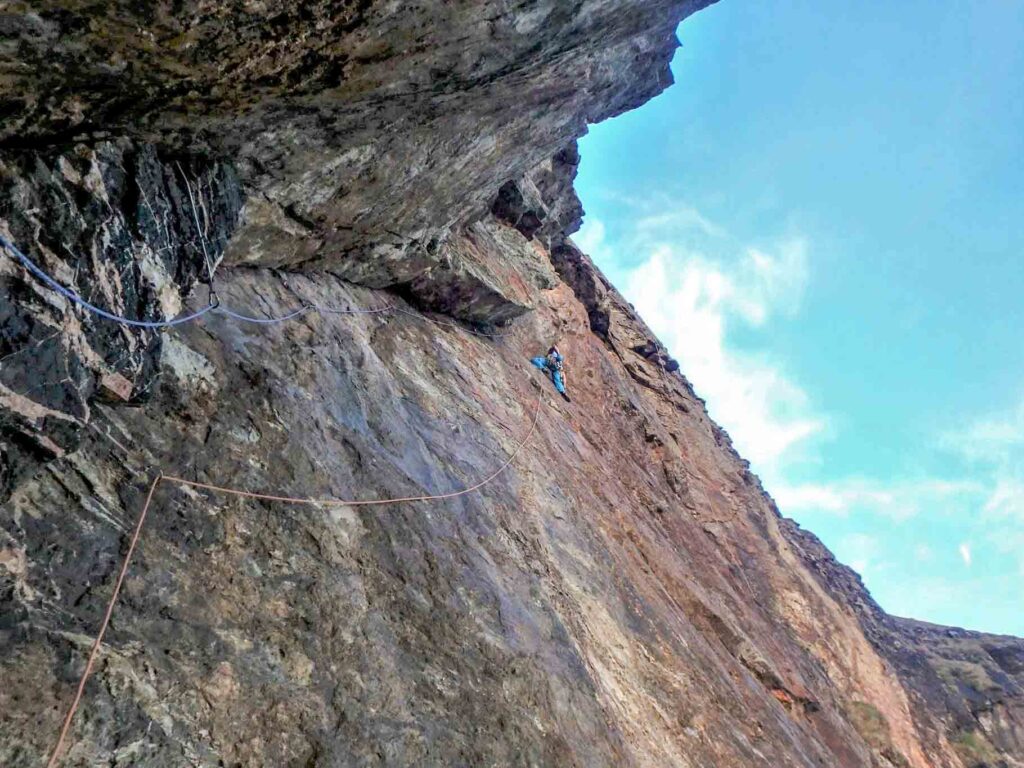

The area is notorious as one of the most adventurous rock-climbing crags in Cornwall, some say Cornwall’s answer to the cliffs of Gogarth in North Wales. As such, I have climbed here many times, and have always been fascinated to think what coasteering those cliffs would be like. Extremely committing, with no ways up or down for a very long way, it would surely offer a great coasteering adventure.

Heading further up the coast, I have heard claims of what could be Cornwall’s longest sea cave, so I’m definitely excited to check that one out, as soon as possible.

On the south coast, the Lizard peninsula would be next. I have coasteered on the Lizard before only a handful of times, but it was very good stuff. With only 20 miles of coast path, that makes it roughly half the size of Penwith. I’d have to look more closely, but a dozen concerted efforts could potentially tick the entire Lizard Peninsula off.

Beyond the Fal estuary, from the Roseland peninsula and beyond, I don’t know the coast well at all. I suspect much of it is similar to Carbis Bay, inasmuch as, being significantly more sheltered from swells than the rest of Cornwall, it is possible that this has not led to well-developed sections of coastline suitable for coasteering.

Closer to home, some of the offshore islands near the coast of West Penwith offer some good coasteering challenges. They would also pose logistical challenges, as it would be necessary to access these locations by boat and, in some cases, have boat support throughout.

On an unusually calm summer’s day, it would be great fun to do some coasteering around the archipelago of Carn Bras, better known as the Longships. Situated approximately one mile off Land’s End, particular on a low spring tide, there is an awful lot of rock visible, just begging to be scrambled on and jumped off! I’m sure serious currents flow between the individual islands. As the only practical way to reach the islands for a coasteer would be by boat, you’d, handily, have boat support the whole way, just in case you started drifting off into the open Atlantic!

Situated one mile off Cape Cornwall, the twin islands of the Brisons would offer another fine day out. As Cornwall’s answer to Devil’s Island from the novel, Papillon, it is said that the Brisons were used in older times as a prison. As such, their name is possibly derived from the Cornish word ‘brissen’, meaning ‘prison’. From my vantage point on a Skybus flight, returning from a day of coasteering on the Isles of Scilly, it looks like there might be an epic cliff jump in a square cut zawn on the back of the larger island, too!

West Cornwall Non-Stop: The Ultimate Coasteering Challenge

So, it’s an understatement to say that there’s still plenty more exploration in the offing! But what else? I have to wonder, when people think I must mean that I coasteered the coastline of west Cornwall in one go, would that even be possible? It certainly wouldn’t be possible in a single push, but could it be done as a single, multi-day endurance event? It could make an interesting challenge!

As I said previously, the area covered in project Penwith consisted of twenty-odd single sessions. If you could cover two of these in a day, it might be possible to do the whole lot in two weeks. If you could do three legs per day (I think this might be unlikely, at least to keep up with day after day), it could be done in ten days or less!

To make the challenge more authentic, I’d work within some additional parameters. Firstly, the coasteering challenger, or challengers, would not be able to leave the coast for the duration of the challenge. Maybe not even crossing the high tide line! This would mean traversing those sections of coast that had been omitted from Project Penwith. So, crossing all the beaches and the torturous miles of boulder beaches previously avoided. In the midst of the coasteering challenge, these might be welcome breaks from the water.

But, we’ve missed something huge. The above parameters mean, that as well as covering the terrain without leaving the coast, it’d be necessary to overnight close to sea level, too. Maybe taking advantage of the hidden nooks and crannies I’ve discovered along the coastline. Carrying the necessary extra clothes, camping equipment, food and water would be impossible. So only with a separate support team would it be possible.

It all sounds a but fantastical, and I doubt I’ll ever actually be motivated to do it. One final factor makes the idea go from the sublime to the ridiculous. The weather. Only in fair weather would the challenge be realistic, especially for the north coast. It’s rare to get a calm spell that lasts more than a few days. And if a prolonged calm spell did occur, it’s seems unlikely a willing team would be ready to go at the drop of a hat. It still makes for an intriguing thought, if anyone out there fancies giving it a go, drop me a line!