Everything You Need to Know About Climbing Ropes

If you’re looking to buy your first climbing rope, or upgrade your setup as you branch into different styles, this guide breaks down what you need to know.

We’ll cover rope types (single, half, twin, static), sizing, diameter, dry treatment, and more, helping you choose the right climbing rope for your needs.

This post is part of a four-part series on buying climbing gear, but it stands on its own. If you’re still deciding on shoes, harnesses, or protection, you’ll find links to those guides throughout.

Climbing Rope Overview

Climbing ropes are dynamic. They’re designed to stretch slightly and absorb the force of a fall. But not all ropes are the same, and the right choice depends on the type of climbing you’re doing.

There are a few main types to be aware of:

- Single ropes are used on their own and are suitable for most sport, trad, and indoor climbing.

- Half ropes are used in a pair and clipped into alternate pieces of gear. These are typically used on trad or alpine routes.

- Twin ropes are also used in a pair, but both ropes are clipped into every piece of gear.

- Triple-rated ropes are certified for use as single, half, or twin ropes.

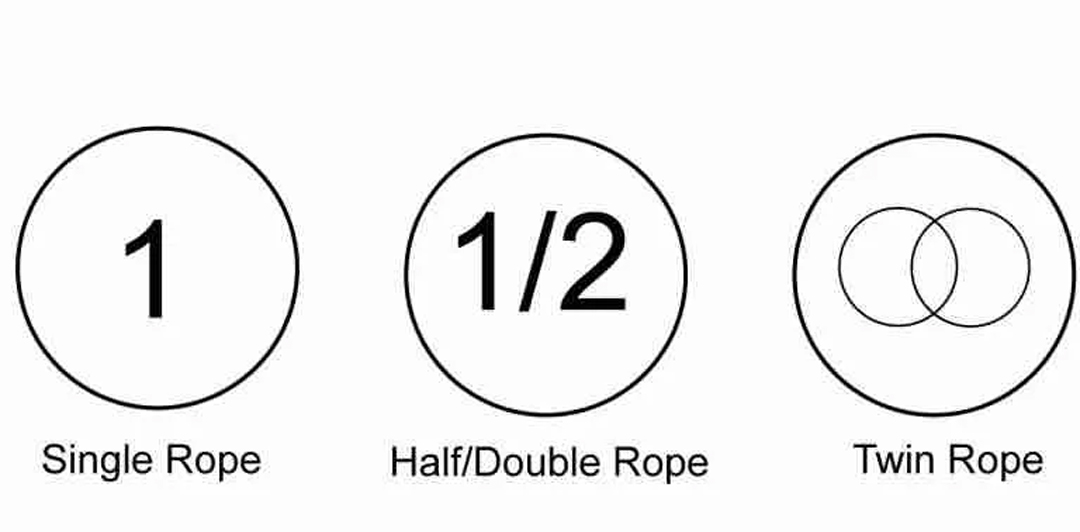

The symbols above represent the official UIAA and EN markings used to certify dynamic climbing ropes. A single circle with a “1” indicates a single rope, suitable for use on its own. The “½” symbol stands for a half rope, which must be used in a pair and clipped alternately into protection. Two interlocking circles indicate a twin rope, also used in pairs but clipped together into each piece of gear. You’ll find these symbols printed on the rope’s end labels and packaging. Always check before use to ensure you’ve got the right type for your intended climbing.

Each type of climbing rope has its place, and we’ll look at them one by one in the sections below. If you’re buying your first climbing rope, don’t worry. It’s more straightforward than it might seem at first.

This post contains affiliate links. If you use these links to buy something we may earn a commission at no extra cost to yourself. Thanks.

Single Ropes: The Go-To Option

At its simplest, if you’re climbing on just one rope, you should be using a single rope. These are the most common type, marked with a “1” symbol. They’re used on their own and are suitable for indoor climbing, sport routes, and many trad climbs too.

At the start of your climbing career, a single-rated rope is the right place to begin. They’re simple to use, easy to handle, and compatible with most climbing styles. The lifetime of a rope is limited, so this won’t be the only one you ever buy — but it will likely be the most versatile.

I’ve used both the DMM Statement and Tendon Smart Lite ropes. Both are reassuringly thick, hard wearing, and handle well straight out of the packaging. They’re available in a range of lengths and are excellent options for a first rope.

Climbing With Half Ropes

Particularly in trad climbing in the UK, it is common practice to use half ropes (also known as double ropes). As the name implies, one of these ropes only makes up half the number of ropes required to climb safely. Owners of a set of half ropes should therefore be aware that they should not climb using only one half rope at any time.

So why would anyone want to use half ropes? The use of two ropes has become common in trad climbing, where routes can often zig-zag across the crag and meander from left to right, following lines of weakness up a rock face. A single rope going through runners at acute angles, around corners, or over roofs, runs a real risk of generating serious rope drag. This can be a genuine show-stopper. Poor rope management on a route can result in the leader being unable to finish a pitch, as they may no longer be able to pull up any rope due to the friction in the system.

However, with careful rope management, climbing on half ropes will eliminate this problem altogether. The trade-off is that half ropes tend to be much thinner than single ropes, to save weight. They are generally not as strong and therefore need to be used in a proper pair.

Twin Ropes

Twin ropes are quite specialist and are usually used by ice climbers. With sharp, pointy things attached to both their hands and feet, and climbing through potentially sharp terrain, ice climbing carries a far greater risk of cutting the rope. As a result, climbers seek the highest level of redundancy possible in their rope system.

Unlike half ropes, which alternate between clipping different pieces of gear, twin ropes are always clipped together into every single piece of protection. This means both ropes run together as a single strand, acting more like a backup system than a way of reducing drag.

Ice routes are typically fairly straight, so rope drag isn’t usually a concern. Instead, the focus is on safety. If one rope is damaged by rockfall or a sharp edge, the second rope provides a critical backup. Twin ropes are also useful for long abseils, where having two strands of equal length is essential.

It’s important to note that twin ropes are not interchangeable with half ropes. Each type must be used as intended, with a compatible belay device.

Triple-Rated Ropes

The final category of ropes are triple-rated ropes. These have passed the tests for all three dynamic rope types: single, half, and twin, and will display all three symbols on their label.

As rope technology has improved, the weight and diameter of triple-rated ropes have become comparable with dedicated half ropes. Unsurprisingly, this level of versatility comes at a price. But for climbers who want one rope system to cover everything, from indoor climbing and sport routes to trad, alpine, and multi-pitch adventures, a pair of triple-rated ropes is a solid investment.

I’ve used Beal Jokers for years. They’re dry-treated, triple-rated, and hard to fault. Another excellent option is the Petzl Volta. If you plan to climb across a range of disciplines, ropes like these are definitely worth considering.

Semi Static Ropes: For Abseiling and Rigging

Climbers use dynamic ropes for some very important reasons. The stretch of these ropes is a required property to be able to climb safely. Taking any kind of fall on a no-stretch rope could have disastrous results.

Firstly, the impact on a falling climber could cause serious injury. The process of the rope stretching during a climbing fall dissipates a huge amount of the force of the fall.

Secondly, this dissipation of forces lessens the force exerted on the hardware that the rope is running through. A hard fall onto gear with a no-stretch rope could cause catastrophic equipment failure.However, there are use cases in climbing where we do not want the ropes to stretch. This is predominantly when abseiling, and for rigging ropes, i.e., for setting up top-ropes and so on.

As loads are repeatedly applied and released from abseil and rigging ropes, there is inevitably a sea-saw effect. This can be greatly amplified by using a dynamic rope. The result could lead to rope damage or failure as the rope is sea-sawed across any edges the rope comes into contact with.

The answer is semi-static, or low stretch ropes. Such ropes have their own certification, EN 1891, or UIAA 107. Semi-static ropes generally come in plainer colours than dynamic ropes, although this is not always the case.

Check the labelling on any rope before use, to ensure you are using the correct rope for your intended use.

Rope Length and Diameter

Like every parameter, this will depend on what situations you’ll be using your rope in. It stands to reason that there’s no point in buying a rope far longer than you’ll ever need. And of course, there’s no sense in buying a rope that’s going to be regularly too short to climb full pitches on the crags you plan to visit.

For example, if you only plan to get the kit needed to climb at your local climbing wall for the time being, simply buy a rope long enough to cater to the longest routes there. Check with the wall, but in many cases, a 50- or even 40-metre rope will be adequate for indoor climbing. Don’t forget to tie a knot in the dead end of the rope.

However, if you’re climbing sport routes outside, a 70- or 80-metre rope is often needed, especially if you’ll be taking sport climbing trips in sunnier climes.

In the UK, trad climbers tend to use ropes of 50- or 60-metres in length. The price difference between the two shouldn’t be much, so a 60-metre rope should cover just about any trad pitch you’re likely to encounter in the UK, leaving extra to build a spaced-out anchor too, if required.

The diameter of your climbing rope will have a fundamental effect on its weight (as does the sheath-to-core ratio). This will only really become important on harder and longer routes. And boy, it certainly does become important. Simply pulling the rope up to clip a piece of gear 40 metres into a pitch can become a serious effort. That’s the last thing you need on a long, endurance-sapping test piece.

At the cutting edge (pun intended), ropes can be less than 8mm in diameter. Whilst this may be appealing, thinner ropes are much quicker to wear out and, God forbid, more likely to be cut through if loaded over a sharp edge.

Thus, for your first rope, I’d go for a chunkier rope of between 9 and 10mm. Too thick, and rope handling may become an issue itself. But until shaving off weight becomes important to you, enjoy using a beefy rope that can take a bit of abuse. Your first rope should be a single rope. ‘Single rope’ specifically refers to its rope type.

Dry Treatment and Rope Construction

All modern climbing ropes are kernmantle ropes — meaning they have a strong inner core (the “kern”) and a protective woven outer sheath (the “mantle”). The core takes most of the load, while the sheath adds durability, handling, and protection. Rope manufacturers vary the balance of sheath-to-core ratio to optimise for different types of climbing. Heavier sheaths tend to mean more durability but also more weight.

Top-end climbing ropes may also be dry-treated. Dry treatment adds an element of water repellence to the ropes, which offers a number of advantages.

Absorbing much less water, they won’t get heavier when climbing in wet (or icy) conditions. Dry-treated ropes will also have a longer lifespan. Wet ropes wear out faster than dry ones, especially with respect to stresses from falls. Dry treatment also lessens absorption of dirt and other particles that will contribute to the ageing and wearing of your rope too.

Whilst there are few real downsides to dry-treated ropes, expect to pay more for a dry-treated rope versus a non-dry-treated one. However, given the longer life expectancy of a dry-treated rope, I think they’re a good idea for any kind of outdoor climbing.

In addition, for anyone who spends time climbing sea cliffs, where salt is a constant problem, dry treatment can only be a good thing. However, if your ropes end up in a salty rockpool, dry-treated or not, make sure you give them a wash in fresh water as soon as you get home.

Ultimately, you want to buy a single rope, or pair of ropes, that are going to cover most — if not all — of the climbing situations you envisage in the near future. If you only see yourself climbing indoors for the time being, there’s no point buying a pair of triple-rated, dry-treated ropes. But if you have ambitions to progress to outdoor climbing as soon as possible, you might want to factor that into your plans to avoid buying twice.

Caring for Your Rope

A climbing rope is one of the most expensive and critical pieces of gear you’ll own, so it’s worth taking care of it properly.

First and foremost, keep your rope clean and dry. Dirt and grit can work their way into the sheath, accelerating wear over time. Using a rope bag is one of the easiest ways to keep it off the ground and protected at the crag or wall.

Avoid standing on your rope. Grit on the soles of your shoes can grind particles into the rope fibres, weakening it from the inside. This kind of hidden damage isn’t always visible, but it adds up.

Store your rope loosely coiled in a cool, dry place away from direct sunlight, chemicals, and sharp objects. UV exposure and high heat can degrade the materials over time.

Inspect your rope regularly. If the sheath is frayed, if you feel flat spots, or if you’ve taken a significant fall, it’s worth checking with a more experienced climber or gear shop. In some cases, you may need to retire it even if it looks OK on the outside.

Most rope manufacturers recommend a maximum lifespan of ten years from the date of manufacture, even if the rope has never been used. Ropes that see regular use will reach the end of their life much sooner. Always follow the manufacturer’s guidance, and when in doubt, retire it.

Standard guidance is:

- Immediate retirement if damaged, heavily worn, exposed to chemicals, or involved in a severe fall.

- 10 years maximum from the date of manufacture (not purchase), even if unused and properly stored.

- 5–10 years with occasional use and good care.

- 1–3 years for frequent use or use in harsh conditions.

Examples from top brands:

- Petzl: 10-year max lifespan, unused or not.

- Beal: 10 years maximum, plus a recommended 3–5 years of use for frequent climbers.

- Edelrid: 10 years maximum from manufacture, 3–6 years with careful use.

Washing Your Rope

If your rope picks up a lot of dirt, chalk, or salt (especially after sea cliff climbing), it’s a good idea to wash it. Rinse your rope in cool or lukewarm water in a bathtub or large container. Gently agitate it by hand, but never use a washing machine with an agitator, as this can damage the fibres.

For a deeper clean, use a rope-specific wash like Beal Rope Cleaner or Nikwax Tech Wash. Never regular detergent or soap, as these can degrade the rope’s materials.

After washing, hang the rope loosely in a shaded, well-ventilated area until completely dry. Avoid radiators or direct sunlight, which can weaken the fibres.

Climbing Rope Types: Quick Comparison

|

Rope Type |

Use Case |

Key Advantage |

Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Single Rope |

Sport, trad, indoor |

Simple and versatile |

Heavier on long routes |

|

Half Ropes |

Trad, alpine, sea cliffs |

Reduces rope drag |

Requires more skill and management |

|

Twin Ropes |

Ice, alpine |

Maximum redundancy |

Both ropes must be clipped together |

|

Triple-Rated |

Mixed use (sport, trad, alpine) |

Can be used in any configuration |

More expensive, often thinner |

|

Static Rope |

Abseiling, rigging |

No stretch, ideal for fixed lines |

Unsafe for lead climbing |

Climbing Rope FAQs

Final Thoughts on Choosing the Right Rope

There’s no perfect climbing rope, just the right rope for the type of climbing you plan to do.

If you’re just starting out, focus on simplicity and durability. A beefy single rope of around 9.8–10mm and 60 metres in length will cover almost any situation, from the indoor wall to your first trad leads. As you progress and diversify your climbing, you’ll naturally end up adding to your rope collection.

Consider where you want your climbing to take you. If sea cliffs, icy north faces, or long adventurous trad routes are on your radar, it might be worth investing in dry treatment or even triple-rated ropes. Yes, you’ll pay more, but you’ll only need to buy once.

Finally, don’t forget: ropes don’t last forever. Keep an eye on wear and tear, log any big falls, and retire your ropes when the time comes. And always wash them off if they’ve been swimming in the sea.

Now you have gained a better understanding of the various rope types out there, jump to our other articles on range of climbing equipment needed for various types of climbing, from indoor climbing, to sport and trad climbing.

By Matt – Trad Climber, Instructor & Founder of Kernow Coasteering

Matt George is the founder and lead instructor at Kernow Coasteering. Climbing since 2008, he cut his teeth on the sea cliffs of West Cornwall and never looked back. Almost all of his climbing is trad — a product of the adventurous local ethic and the wildly exposed terrain that defines the Cornish coast.

When he’s not leading clients or writing about gear, Matt can be found exploring obscure zawns, or dangling an outrageous number of large cams off his harness en route to another off-width battle. If you’re looking for trad climbing gear advice from someone who’s been there and placed it, he’s your guy.